Literary and historical notes of a young technician. Yakov Slashchev: how the White Guard hangman general became the mentor of the Red Army Budyonny Slashchev

Many people remember the scene from Mikhail Bulgakov's "Running", where General Khludov commands his orderly: "Show the minister a working deputation!" He leads the minister into the yard, where corpses swing on the gallows...

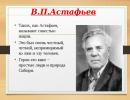

The prototype of General Khludov was General Yakov Aleksandrovich Slashchev. He really hung and shot in packs those who violated military order and discipline, not to mention enemies. But beyond that, he was a brave combat commander.

Slashchev was extremely popular among his soldiers, who affectionately called him "General Yasha." And he was hated by those who, under the cover of the White Guard uniform, sat in the rear, speculated, profited.

Battle path

To the first world war Slashchev rose to the rank of colonel, was wounded five times, and was awarded the Order of St. George and the St. George weapon for personally leading the troops on the attack. The pain from the many wounds (several more were added during the Civil War) contributed to the formation of his addiction to drugs, which were used against him by his personal enemies.

Shortly before October revolution Slashchev retired, seeing how the army was falling apart. But he was going to fight the Bolsheviks and went to the Don, where he took part in the creation of the Volunteer Army. In 1918 he helped the Kuban partisan Colonel Shkuro. Their dashing Cossack detachment smashed the rear of the Reds, liberated the city of Stavropol and joined the army of General Denikin.

AT armed forces South of Russia, Slashchev received the rank of general for a successful landing operation in the spring of 1919 in the Koktebel region, after which the Whites liberated Crimea from the Reds. His finest hour came in January 1920, when his prefabricated, poorly armed units repulsed the attacks of the Reds on the Perekop Isthmus.

Once, Slashchev's troops faltered and already leaned back. The general ordered the banners to be deployed, the orchestra to play a march, and personally led the troops in a "psychic attack" on the Reds. Here the enemy could not stand it and ran.

Crimea became the last refuge of the White Army for almost a year. And for Slashchev, the glory of the savior of the Crimea was established.

Enmity with Wrangel

General Wrangel in his memoirs paints a portrait of General Slashchev as a rapidly degraded personality. “His addiction to wine and drugs was well known...,” he wrote. - I saw him for the last time near Stavropol, he struck me then with his youth and freshness. Now it was difficult to recognize him ... His fantastic costume, loud nervous laughter and erratic jerky conversation made a painful impression.

Wrangel wrote his Notes after Slashchev had betrayed the White Cause and returned to Soviet Russia. Those who saw Slashchev later, in “red” Moscow, speak of him as adequate and interesting person. Wrangel obviously went too far, trying to draw the repulsive appearance of his popular rival. Everyone knew that even in the white Crimea, irreconcilable differences arose between the two military leaders.

And no wonder. Slashchev, in his own way, cruelly but effectively, fought the decay of the troops and the rear. Moreover, he constantly interfered in politics, annoying the commander-in-chief with reports about the need for repression, and earned a reputation as an ardent monarchist. Wrangel believed that Slashchev was discrediting the White movement in relations with the Entente.

Slashchev-Krymsky

Slashchev was a landing master. In June 1920, thanks to his successful operations, the White Army left the Crimea for operational space. But on political reasons Wrangel in August 1920 entrusted the execution of the landing in the Kuban to the Cossack general Ulagai. The landing failed.

Slashchev, at that time, was thrown into an unprepared assault on the fortified Red bridgehead near Kakhovka. The assault also failed. Wrangel accused Slashchev of disintegrating the troops and removed him from command. The dismissal was given the appearance of an honorable resignation, and Wrangel allowed Slashchev to add the name Krymsky to his surname.

In November 1920, when leaving the Crimea, Wrangel tried to detain Slashchev at the front under the pretext of organizing partisan detachments. But Slashchev-Krymsky made his way to the evacuation along with his fighting girlfriend and common-law wife, Nina Nechvolodova, who wore two St. George crosses (however, the circumstances of their receipt are unknown).

To Moscow in Dzerzhinsky's carriage

In Constantinople, Slashchev sharply opposed Wrangel, accusing him of the Crimean failure. In response, Wrangel initiated a "court of honor" that expelled Slashchev from the Russian army.

At that time, it was important for the Bolsheviks to find a popular White Guard commander who could split the emigration from the inside. Agents of the Cheka in advance contacted Slashchev, using his hatred for Wrangel. It is not known exactly when this happened, but there is evidence that Dzerzhinsky himself personally raised the issue of Slashchev's return to Soviet Russia at a meeting of the Politburo. A slight majority supported Dzerzhinsky, although Lenin himself abstained.

In November 1921, after a year of exile, Slashchev and his wife and with them several military and civilian emigrants returned to Sevastopol. White General arrived in Moscow in the personal carriage of the chairman of the Cheka.

In January 1922, the Soviet press published Slashchev's appeal to all white emigrants, calling for them to return to Soviet Russia. “Otherwise, you will turn out to be mercenaries of foreign capital ...,” he inspired them Crimean hero. "Don't you dare sell yourself to go to war with Russia."

Slashchev's appeal had an effect on a significant part of the white officers and soldiers interned in Turkey and Poland. Many thousands repatriated in the first months of 1922.

"The way you shoot is the way you fight"

Slashchev repeatedly wrote reports with a request to send him to the combat unit, but he was left to teach at the courses commanders Red Army "Shot". The future Soviet Army General Batov recalled that Slashchev's lectures on tactics invariably aroused great interest among the audience.

Before the revolution, Slashchev did not excel in the sciences - he graduated from the Academy of the General Staff one of the last in terms of academic performance. But the downside theoretical knowledge was replenished by the former general with rich combat practice. He had something to tell his former enemies.

On this basis, conflicts often arose. It was said that once, in the presence of Budyonny, Slashchev sharply criticized the actions of the Red Command in the Polish campaign. Budyonny pulled out a revolver and began to shoot, but missed drunk. Slashchev calmly said to the commander of the First Cavalry: "The way you shoot is the way you fight."

The trail of blood that the general left behind in the Civil War returned like a boomerang. In January 1929, Slashchev-Krymsky was shot dead in his room by a certain Lazar Kolenberg. The killer motivated his act with revenge for his brother, who was allegedly hanged on the orders of Slashchev in 1919 in Nikolaev. The killer was declared insane and released from punishment.

Yaroslav Butakov

Developments

18 January 1915 child birth: Vera Yakovlevna Slashcheva [Slashchevy] b. 18 January 1915

Notes

Yakov Aleksandrovich Slashchev-Krymsky (Russian doref. Slashchov, December 29, 1885 - January 11, 1929, Moscow) - Russian military leader, lieutenant general, an active participant in the White movement in southern Russia.

"Slashchev (Slashchov) is the same White Guard hangman general who became the prototype of Khludov for Mikhail Bulgakov. When Denikin retreated to the Caucasus after the defeat of the Red Army, Slashchev occupied the Crimea and organized an effective defense of the isthmuses. He was the undivided ruler of the Crimea, while the Military Council did not elect Wrangel as the new commander (Slashchev defiantly ignored this meeting.) He had his own view on the conduct of further military operations against the Reds, wrote reports to Wrangel, which the latter perceived as nothing more than the delirium of a madman (/ see below a fragment from Wrangel's memoirs /). biography of Slashchev began to return to Soviet Russia a year after the evacuation from the Crimea. He was given to write and publish a book of memoirs "Crimea", an appeal to the White Guards who remained in exile, but they did not take leadership positions in the Red Army. They gave him a teaching position at the school of commander tactics "Shot".

They say that during the analysis in the classroom of the Soviet-Polish war, in the presence of Soviet military leaders, he spoke about the stupidity of our command during the military conflict with Poland. Budyonny, who was present in the audience, jumped up, pulled out a pistol and fired several times in the direction of the teacher, but missed.

Slashchev approached the red commander and said instructively: "The way you shoot is the way you fought." Or maybe this episode is hyperbole.

Slashchev died at the hands of Kolenberg, whose brother was executed on his orders in the civil war. Liberal historiography has no doubts that these were the intrigues of Stalin's agents. However, there is every reason to believe that there was no politics in this murder, only personal revenge."

He was not afraid of his revenge former enemies and their relatives. Slashchev had long been ready for death. He saw her too often. On January 11, 1928, Yakov Alexandrovich Slashchev was killed by a pistol shot by a certain Kolenberg, whose brother was hanged by order of the general. Three days later, the general's body was burned in the Donskoy Monastery. For a whole generation, Slashchev forever remained the last symbol Great Russia. A symbol of cruel, mistaken, but not broken.

Yakov Alexandrovich Slashchev-Krymsky(Russian doref. Slashchov, December 29, 1885 - January 11, 1929, Moscow) - Russian military leader, lieutenant general, an active participant in the White movement in southern Russia.

Biography

He was born on December 29 (according to another version - December 12), 1885 in St. Petersburg in the family of hereditary nobles Slashchev. Father - Colonel Alexander Yakovlevich Slashchev, hereditary military man. Mother - Vera Alexandrovna Slasheva.

In 1903 he graduated from the Gurevich real school with an additional class.

Imperial Army

In 1905 he graduated from Pavlovsk military school, from where he was released as a second lieutenant in the Life Guards Finnish Regiment. December 6, 1909 promoted to lieutenant. In 1911 he graduated from the Nikolaev military academy in the 2nd category, without the right to be assigned to the General Staff due to an insufficiently high average score. On March 31, 1914, he was transferred to the Corps of Pages with the appointment of a junior officer and enrollment in the Guards Infantry. AT Corps of Pages taught tactics.

On December 31, 1914, the Finnish Regiment was re-assigned to the Life Guards, in the ranks of which he participated in the First World War. He was wounded twice and wounded five times. Awarded with the St. George weapon:

and the Order of St. George 4th degree:

On October 10, 1916 he was promoted to colonel. By 1917 - assistant commander of the Finnish regiment. On July 14, 1917, he was appointed commander of the Moscow Guards Regiment, a position he held until December 1 of the same year.

Volunteer army

- December 1917 - joined the Volunteer Army.

- January 1918 - sent by General M. V. Alekseev to the North Caucasus to create officer organizations in the region of the Caucasian Mineralnye Vody.

- May 1918 - chief of staff of the partisan detachment, Colonel A. G. Shkuro; then the chief of staff of the 2nd Kuban Cossack division, General S. G. Ulagay.

- September 6, 1918 - Commander of the Kuban Plastun Brigade as part of the 2nd Division of the Volunteer Army.

- November 15, 1918 - commander of the 1st separate Kuban plastun brigade.

- February 18, 1919 - brigade commander in the 5th Infantry Division.

- June 8, 1919 - brigade commander in the 4th Infantry Division.

- May 14, 1919 - promoted to major general for military distinctions.

- August 2, 1919 - Head of the 4th Infantry Division of the Armed Forces of South Russia (13th and 34th consolidated brigades).

- December 6, 1919 - commander of the 3rd Army Corps (13th and 34th consolidated brigades deployed in divisions, numbering 3.5 thousand bayonets and cavalry).

He enjoyed love and respect among the soldiers and officers of the troops entrusted to him, for which he earned an affectionate nickname - General Yasha.

Defense of Crimea

- December 27, 1919 - At the head of the corps, he occupied the fortifications on the Perekop Isthmus, preventing the capture of the Crimea.

- Winter 1919-1920 - Head of the defense of the Crimea.

- February 1920 - Commander of the Crimean Corps (former 3rd AK)

- March 25, 1920 - Promoted to lieutenant general with the appointment of commander of the 2nd Army Corps (former Crimean).

- On April 5, 1920, General Slashchev submitted a report to the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army in the Crimea and Poland, General P.N. Wrangel, indicating the main problems at the front and with a number of proposals.

- From May 24, 1920 - Commander of a successful white landing at Kirillovka on the coast of the Sea of Azov.

- August 1920 - After the inability to liquidate the Kakhovka bridgehead of the Reds, supported by large-caliber guns TAON (heavy artillery for special purposes) of the Reds from the right bank of the Dnieper, he submitted a letter of resignation.

- August 1920 - At the disposal of the commander in chief.

- August 18, 1920 - By order of General Wrangel, he received the right to be called "Slashchev-Krymsky".

- November 1920 - As part of the Russian army, he was evacuated from the Crimea to Constantinople.

In his play "Running" he painted the hangman-general Khludov, whose prototype was none other than the White Guard officer Yakov Alexandrovich Slashchev (Crimean).

Origin. Education

Yakov Alexandrovich was born either on December 12 or December 29, 1885 in the capital - St. Petersburg. His father was a hereditary military man - Colonel Slashchev Alexander Yakovlevich. In 1903, Yakov successfully graduated from a real school and, when the time came to choose a life path, without hesitation, decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, enrolling in the Pavlovsk Military School, which he later graduated brilliantly. From 1905 to 1917 in the Finnish regiment, he went from the usual officer position of company commander to assistant regiment commander. At the same time, during this time, Yakov Alexandrovich managed to graduate from the Imperial Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff.

World War I

During the period, Slashchev was wounded five times and shell-shocked twice, but this did not affect the fact that he always with his regiment in all hot spots found himself in the thick of things. In 1915, Slashchev married the daughter of General Kozlov, the regiment commander. It cannot be said that this marriage was carried out not without the mercantile considerations of Slashchev. It was just that at some point he realized that only with the help of the Academy of the General Staff, brilliant military career he can’t do it, and therefore he became related to the higher authorities.

But already in 1918, Yakov Aleksandrovich met a very nice cadet named Nechvolodov, who served as his orderly. Nechvolodov's orderly turned out to be eighteen-year-old Nina Nechvolodova, for whom Slashchev fell in love. During, Nina was always there, despite several injuries, she never left her general. They formalized their relationship in 1920. In the same year, the pregnant Nina was captured by the Bolsheviks, which gave Slashchev the opportunity to appreciate his ideological enemies. When the Chekists recognized in Nina the wife of one of the most ardent opponents Soviet power, they decided to shoot the woman, but Dzerzhinsky intervened, who, after interrogation, acted nobly: he sent her over the front line to her husband.

Slashchev was nicknamed "Crimean", for a reason. When Denikin, pressed by the "Reds", retreated to the Caucasus, General Slashchev occupied the Crimea, where he organized a very effective defense of the isthmuses. He reigned supreme on the Crimean peninsula. In general, Slashchev, also during his reign in the Crimea, earned himself the fame of a cruel executioner, due to mass executions. However, he appreciated the general, and it was he who gave Slashchev the name "Crimean". In 1920, like many other officers, he was evacuated to Constantinople, ousted from the Crimea by the Red Army.

In Constantinople, General Slashchev, along with his wife Nina, was engaged in growing vegetables for sale in one of the markets. They lived in a hut on the outskirts of the city. Yakov Alexandrovich tried not to get involved in politics. The White Guards did not like him, mindful of his obstinacy and autocratic rule, and the Red Army men frankly hated him because of the mass executions that he committed in the Crimea. And who knows how Slashchev's fate would have developed further if thunder had not struck in the clear sky of Constantinople: Wrangel called for an agreement with the Entente.

Slashchev could not stand this and declared publicly that he would support the Bolsheviks, and demanded a fair trial of Wrangel for treason. Wrangel's reaction was instantaneous: he demoted General Slashchev to the rank and file. Dzerzhinsky's reaction was also not long in coming: he invited Slashchev to return to his homeland from Turkish exile. Slashchev's wife, remembering how Felix had once nobly released her from captivity, persuaded her husband to return, join the Red Army, assuring her husband of the nobility of the "Reds".

Upon his return, Slashchev began teaching at the Military Academy, where he mercilessly ridiculed the military campaigns of the Red Army when they tried to take the Crimea, which Slashchev also held. Soon he was transferred to teach at the Shot school, because not all students and teachers of the Academy could withstand General Slashchev. Once Budyonny almost shot Slashchev right during a lecture, when he, in his usual ironic and mocking manner, painted all the tactical disadvantages of one of the offensives undertaken by Budyonny. He, unable to withstand the ridicule, jumped up and fired at Slashchev five times, never hitting the target. To which Slashchev, calmly approaching Budyonny, remarked, they say, that's how you shoot, that's how you fought. At the same time, Slashchev collaborated with a military magazine, in which he published brilliant articles on military strategy.

Death

In January 1926, Yakov Aleksandrovich was shot dead by a certain Kolenberg, 24 years old. When Kolenberg was captured, he said that the murder of the former White Guard general was a personal revenge. Among the many Red Army soldiers shot by Slashchev in the Crimea was the brother of the killer. This served as an excuse for Kolenberg, and soon the killer was released.

SLASHCHEV

(Slashchev-Krymsky, another spelling of the surname: Slashchov), Yakov Alexandrovich (1885 / 1886-1929), lieutenant general of the White Army, prototype of Khludov and some other characters in Bulgakov's play "Running". Born December 29, 1885 / January 10, 1886 in St. Petersburg in the family of a retired colonel, from hereditary nobles. In 1905 he graduated from the Pavlovsk Military School and began serving in the Finnish Life Guards Regiment. In 1911 he graduated from the Imperial Nikolaev Military Academy (former Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff), but without the right to be assigned to the General Staff. Bulgakov, judging by the words of Charnota addressed to Khludov: “Roma, you are the General Staff! What are you doing?! Roma, stop!”, (we are talking about extrajudicial executions), allows the character to achieve greater success in the Academy than his prototype (S. graduated from the Academy in the 2nd category with an average score of less than 10, and those who graduated from 1 th category, with an average score of 10 and above). Since 1912, Mr.. S. taught tactics in the Corps of Pages. By his first marriage, S. was married to the daughter of the commander of the Life Guards of the Finnish Regiment, Lieutenant General Vladimir Apollonovich Kozlov (1856-1931), Sofya. On January 18, 1915, the couple had a daughter, Vera. Father-in-law's patronage may have contributed to S.'s career. From January 1915, S. was in the army, where he rose from a company commander to a battalion commander of the Life Guards of the Finnish Regiment. On November 12, 1916 he was promoted to colonel, and on July 14, 1917 he was appointed commander of the Moscow Guards Regiment. S. was a brave officer, during the First World War he had five wounds, was awarded many orders, including the St. George's weapon and the Order of St. George 4th degree. On December 8, 1917, he retired from the regiment due to being wounded, not wanting to continue serving under the Bolsheviks, and on January 5, 1918, he arrived in Novocherkassk, where Volunteer army generals M. V. Alekseev (1857-1918) and L. G. Kornilov (1870-1918). Commanded by M. V. Alekseev to the region of the Caucasian Mineral Waters, where he became the chief of staff in the detachment of A. G. Shkuro (Skins) (1887-1947), then commanded the 1st Kuban plastun brigade and was chief of staff of the 2nd Kuban Cossack division . In April 1919, S. was promoted to Major General by Commander-in-Chief Lieutenant-General A.I. Denikin (1872-1947) and appointed commander of the 5th Infantry Division, then the 4th Infantry Division and the 3rd Army Corps, which operated in the fall 1919 against the Ukrainian army of S. V. Petliura and the rebel peasant detachments of N. I. Makhno (1889-1934). S. successfully fought against the Makhnovist detachments, but the figure of Makhno possessed a certain attraction for him, he felt in him a kindred adventurous streak. According to a contemporary, S. more than once told his subordinates: "My dream is to become the second Makhno." In the last days of the defense of the Crimea, he even tried to materialize this dream, standing at the head of a partisan detachment in the rear of the Reds after the capture of Perekop by the Soviet troops, but did not receive the support of the commander-in-chief of the Russian army, Lieutenant General Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel (1878-1928). In January - March 1920, the S. corps successfully repelled the attempts of the Red Army to seize the Crimea, for which in April S. was promoted to lieutenant general by P.N. Wrangel, and in June he carried out a successful landing in Northern Tavria. In August 1920, Mr.. S. after unsuccessful battles near Kakhovka filed a letter of resignation. P. N. Wrangel awarded him the title of Slashchev-Krymsky. S. was left at the disposal of the commander-in-chief and sent to Yalta for treatment. In October 1920, in connection with the breakthrough of the Reds into the Crimea, S. went to the front in Dzhankoy, but did not receive any position in the troops. The idea to land behind enemy lines amphibious assault of the volunteers for the development of partisan operations in Northern Tavria, following the example of Makhno, Wrangel did not support him, suggesting that S., if he wished, independently remain behind enemy lines in the Crimea. S., not accepting this offer, left for Sevastopol, from where, on the icebreaker "Ilya Muromets", together with the remnants of his native Finnish Life Guards Regiment and the regimental St. George's banner, he left for Constantinople. In connection with S.'s letter to the committee of public figures on December 14, 1920, with sharp criticism of Wrangel's actions in the defense of the Crimea, the court of honor created by the latter dismissed S. from service without the right to wear a uniform. In response, in January 1921, S. published the book “I demand the court of society and publicity”, where he spoke about his activities at the front and accused Wrangel of the loss of the Crimea. After his dismissal from the Russian army, the Zemsky Union provided S. with a farm near Constantinople, where he raised turkeys and other livestock, but the former general had no talent for agriculture, unlike military affairs, he had almost no income and was very poor from the second wife, Nina Nikolaevna, who was previously listed under him as "orderly Nechvolodov", and his daughter. In February 1921, contacts with S. were established by J. Tenenbaum, authorized by the Cheka, who lived in Constantinople under the surname Yelsky. In May 1921, the Chekists intercepted a letter from the famous journalist and public figure F. Batkin from Constantinople to Simferopol to the artist M. Bogdanov, where it was reported that S. was in such a beggarly state that he was inclined to return to his homeland. Batkin and Bogdanov were recruited by the Cheka, and the latter was sent to Constantinople, but, having come to the attention of the Wrangel counterintelligence, he returned back. Bogdanov was even put on trial for negligence. S. tried to get himself a safe-conduct guaranteeing personal immunity and the allocation of currency to his family, who remained in exile. The former general was refused, and S. himself admitted that no letter would save him from the avenger, if one appeared (he accurately predicted his fate). S. was promised forgiveness and a job in his specialty - a teacher of tactics. F. Batkin managed to secretly put S. with his family and a group of officers who sympathized with him on the Italian ship Jean, which arrived in Sevastopol on November 11, 1921. Here S. was met by the head of the Cheka, F. E. Dzerzhinsky, and taken to Moscow in his personal train. A characteristic note by L.D. Trotsky to V.I. Lenin on November 16, 1921 in connection with the return of S.:

“The Commander-in-Chief (S. S. Kamenev (1881-1936). - B. S.) considers Slashchev a nonentity. I'm not sure if this review is correct. But it is indisputable that with us Slashchev will be only "restless uselessness." He won't be able to adapt. Already on Dzerzhinsky's train, he wanted to give someone "25 ramrods."

The materials in the registry about Slashchev are large (we are talking about documentary evidence crimes of S., collected in the registration department of the Revolutionary Military Council - that was the name of military intelligence at that time. - B.S.). Our polite response (we welcome future employees) is still diplomatic in nature (Slashchev is still going to drag the generals along with him).

The book of Rakovsky (meaning the memoirs of G. N. Rakovsky “The End of the Whites. From the Dnieper to the Bosporus (Degeneration, Agony and Liquidation)”, published in Prague in 1921 and well known to Bulgakov; there, in particular, a characteristic ditty is given “ smoke comes from the executions, then Slashchev saves the Crimea. ”- B.S.) send it, please: I didn’t read it.”

Thus, it was not repentance and a spiritual upheaval, but the calculation to adapt and get a livelihood, as well as the desire to be able to do his beloved military business (he did not know how to do anything else) brought S. to Moscow. In his eyes, Wrangel was to blame for the fact that he lost the Crimea and deprived S. of the opportunity to fight at the head of the troops against the Bolsheviks, and only in the second place - by the fact that he expelled S. from the army. This was fully reflected in the book “I demand the court of society and publicity”, where P. N. Wrangel, A. P. Kutepov (1882-1930), P. N. Shatilov (1881-1962) and other generals were accused not as carriers of vicious white idea and accomplices of France and other foreign powers (as it was in the second book of S.), but for allowing a catastrophe in the Crimea and finally ruining the white cause. S. Bulgakov was well acquainted with the book published in Constantinople. It cited the Constantinople (Istanbul) address of S.: “Veznedzhiler quarter, De-Runi street, Mustafa-Effendi house, No. 15-17.” In Bulgakov's story "The Diaboliad", written in 1923, even before meeting L. E. Belozerskaya, who visited Constantinople, one of the prominent characters, the secretary of the Soviet chief Comrade Chekushin, Lidochka de Rooney, bears such a surname, undoubtedly in connection with book S.

Contrary to Trotsky's fears, S. in the USSR managed to adapt and even make a career. Upon arrival at home, he declared, as reported in the Helsingfors newspaper Put on November 26, 1921: “Not being myself not only a communist, but even a socialist, I regard the Soviet government as a government representing my homeland and the interests of my people. It defeats all the movements that spring up against it, and therefore satisfies the demands of the majority. As a military man, I am not a member of any party, but I want to serve my people, with a pure heart I submit to the government put forward by them. On November 20, 1921, Izvestia published S.'s appeal to the officers and soldiers of the Wrangel army: “Since 1918, Russian blood has been shed in internecine war. All called themselves fighters for the people. The white government turned out to be insolvent and not supported by the people - the whites were defeated and fled to Constantinople. Soviet power is the only power representing Russia and her people. I, Slashchev-Krymsky, call you, officers and soldiers, to submit to Soviet power and return to your homeland. S. was popular, many believed him and the amnesty of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee announced on November 3, 1921, arguing that if S.'s crimes were forgiven, then smaller ones would not be put on the line at all. In fact, unlike S., many of those who returned, especially if they were not very well-known persons, were repressed. S. from June 1922 became a teacher of tactics, and in 1924 he became the chief head of teaching tactics at the Higher Tactical Rifle School for Command Staff "Shot". According to some reports, S. taught in high school OGPU. In 1924, S.'s book "Crimea in 1920: Fragments from Memoirs" was published, which became Bulgakov's main source when creating the image of Khludov in the play "Running". On January 11, 1929, S. was shot dead in his apartment by a cadet of the "Shot" B. Kolenberg, who was avenging his brother, who was executed on the orders of S. S.'s murder was covered in newspaper reports. It is possible that the death of the prototype influenced the appearance of the variants of the finale of "Running", where Khludov committed suicide. According to some reports, Kolenberg received a prison sentence for the murder, according to others, he was declared mentally insane. It is possible that the OGPU helped the avenger find his victim, because a year later, in 1930, under the personal leadership of the then head of this department, V.R. about 5,000 former tsarist and white officers who served in the Red Army were arrested, and from the mid-1920s, their accelerated transfer to the reserve began. S., in connection with the noise raised around his name, it would be inconvenient to arrest or dismiss him from service. It is possible that the OGPU decided to get rid of him in another way - by the hands of Kolenberg. Posthumously, in 1929, S.'s book “Thoughts on General Tactics: From personal experience and observations." In addition, S. published a number of articles in Soviet military periodicals and collections. In “Thoughts on General Tactics”, the final phrase very accurately expressed the military, and even life, creed of S. will lead to defeat."

Probably already in Bulgakov's story "The Red Crown" (1922) S. served as one of the prototypes of the hanging general. Obviously, Slashchev's orders cited in the book "I demand the judgment of society and publicity" also influenced the image of Khludov in "Running" (1928). In this book, unlike the memoirs of 1924, it was not yet necessary to retouch executions at the front and in the rear, repressions against the Bolsheviks and those suspected of sympathizing with them, so the lines of orders sounded menacing: “... I demand that every criminal who propagandizes Bolshevism be extradited ... "" How to protect and punish I will be able to. Introduce the strictest discipline ... Disobedient, beware! According to L. E. Belozerskaya, he was not personally acquainted with S. Bulgakov, but the book “Crimea in 1920” was a desktop when writing "Run". It is curious that L. E. Belozerskaya herself, while still in Petrograd, met S.'s mother, Vera Aleksandrovna Slasheva, and remembered "Madame Slasheva" as a powerful and decisive woman. In the preface to the memoirs of S. famous writer and political worker Dmitry Furmanov (1891-1926) cited the following words of the general: “A lot of blood has been shed ... many grave mistakes have been made. Immeasurably great is my historical guilt before workers' and peasants' Russia. I know it, I know it very much. I understand and see clearly. But if, in a time of grave trials, the workers' state again has to draw its sword, I swear that I will go in the forefront and prove with my blood that my new thoughts and views and faith in the victory of the working class are not a toy, but a firm, deep conviction. At the same time, Furmanov himself admitted: “Slashchov the hangman, Slashchov the executioner: history has imprinted his name with these black stamps ... Before his “exploits”, apparently, the atrocities of Kutepov, Shatilov, and even Wrangel himself - all of Slashchov’s associates along Crimean wrestling. S. himself seeks to create in his memoirs the image of a painfully bifurcated person, trying to regain his lost faith and experiencing pangs of conscience for serving the cause, the correctness of which he doubts: “... In my mind, thoughts sometimes flashed that the majority of Russian people are on the side of the Bolsheviks, because it is impossible that they are now triumphing thanks only to the Germans, Chinese, etc., and have we not betrayed our homeland to the allies ... It was a terrible time when I could not say firmly and directly to my subordinates, what I'm fighting for." Tormented by doubts, S. resigns, is refused and is forced to "stay and continue morally rushing about, not having the right to express his doubts and not knowing where to stop." But for him “there was no longer any doubt that the unprincipled struggle continued under the command of persons who did not deserve any trust, and, most importantly, under the dictation of foreigners, i.e. the French, who now, instead of the Germans, want to take possession of the fatherland ... Who are we then? I did not want to answer this question even to myself.

Bulgakov's General Khludov is experiencing the same torment. He still shoots and hangs, but out of inertia, because he thinks more and more that people's love is not with the whites, but without it, victory in the civil war cannot be won. Khludov vents his hatred for his allies by burning “exported fur goods” so that “foreign whores cannot see sable cuffs.” The commander-in-chief, in which the prototype is easily visible - Wrangel, the hangman-general hates, because he involved him in a deliberately doomed, lost struggle. Khludov throws a terrible face into the commander-in-chief's face: "Who would hang, who would hang, Your Excellency?" But, unlike S., who never repented in his memoirs for any of his specific victims, Bulgakov forced his hero to commit the last crime - to hang the “eloquent” messenger Krapilin, who then overtakes the executioner like a ghost and awakens his conscience. All attempts by S. in his memoirs to justify and reduce his executions do not achieve an effect (he claimed that he signed the death warrants of only 105 convicts guilty of various crimes, but Bulgakov, back in the Red Crown, forced the main character to remind the general how many he had sent to death “by verbal order without a number” - the author of the story remembered from his service in the White Army how common such orders were). Of course, Bulgakov could not have known the episode with 25 ramrods from Trotsky’s letter quoted above, although he showed in The White Guard with amazing accuracy that the Reds, the Whites, and the Petliurists used the ramrod as a universal means of communicating with the population. However, the author of "Running" did not believe in S.'s repentance, and his Khludov was unable to refute Krapilin's accusations: "... You won't win the war with strangleholds alone!.. Do you feed on vultures?.. Brave you only hang women and locksmiths!". Khludov’s excuses that he “went to Chongarskaya Gat with music” and was twice wounded (like S., twice wounded in the civil war) only evoke Krapilin’s “yes, all the provinces spit on your music and your wounds.” Here, the idea, often repeated by Wrangel and his entourage, that one province (Crimea) and forty-nine provinces (the rest of Russia) cannot win is reinterpreted in folk form. After this passionate denunciation, the messenger Khludov hangs the messenger, who was faint-hearted, but then Bulgakov grants him, unlike S., painful and difficult, painful and nervous, but - repentance.

The author of "Running" read not only the books of S., but also other memoirs, which told about the famous general. In 1924, in Berlin, the memoirs of the former head of the Crimean Zemstvo, Prince V. A. Obolensky, “Crimea under Wrangel. Memoirs of a White Guard (they were also published in the magazine Voice of the Past on a Foreign Side). S. Obolensky suspected of socialist views and sincerely hated, the head of the Zemstvo, in turn, looked at the "savior of the Crimea" as an adventurer and a sick person. Obolensky left the following portrait of S.:

“He was a tall young man with a shaved, sickly face, thinning blond hair and a nervous smile that revealed a row of not quite clean teeth. He was twitching all the time in a strange way, sitting, constantly changing positions, and, standing, somehow unscrewed wobbled on his lean legs. I don't know if it was a consequence of the injuries or the cocaine use. His suit was amazing - military, but as if of his own invention: red trousers, a light blue jacket of a hussar cut. Everything is bright and flashy. In his gestures and in the intonations of speech, one could feel the artificiality and posturing. This description served as the basis for a remark depicting Khludov's appearance: “... Roman Valeryanovich Khludov sits huddled on a high stool. This man's face is as white as a bone, his hair is black, combed in an eternal indestructible officer's parting. Khludov's snub nose, like Pavel, is shaved like an actor, seems younger than everyone around him, but his eyes are old. He is wearing a soldier's overcoat, he is belted with a belt around it, not like a woman's, not like the landowners belted their dressing gown. Shoulder straps are cloth, and a black general's zigzag is casually sewn on them. The protective cap is dirty, with a dull cockade, mittens on the hands. There are no weapons on Khludov. He is sick with something, this man is sick all over, from head to toe. He frowns, twitches, likes to change intonations. He asks himself questions and likes to answer them himself. When he wants to portray a smile, he grins. He arouses fear. He is sick - Roman Valeryanovich.

All the differences in Bulgakov's remark from the portrait of S. given by Obolensky are easily explained, despite the fact that the similarity is striking. The actor N.P. Khmelev (1901-1945) was intended for the role of Khludov in the Moscow Art Theater, who really had a snub nose and had black hair with an indestructible officer's parting, so remembered by the audience for his performance of Alexei Turbin in Turbin Days. The fact that Khludov's snub was exactly "like Pavel" should have evoked associations with Emperor Paul I (1754-1801), who was strangled by the conspirators, and, accordingly, with Khludov's desire to win the war with strangleholds. The soldier's overcoat, which replaced S.'s flowery suit, on the one hand, immediately dressed Khludov the way he was supposed to appear in Constantinople after his dismissal from the army without the right to wear a uniform (although in Constantinople the general, at the behest of the playwright, changes into civilian clothes). On the other hand, the fact that the greatcoat was not belted in a military way and there was negligence in all Khludov's clothes gave this costume a kind of extravagance, although not as bright as in the prototype costume. S. Obolensky, like other memoirists, explained the morbid condition by the abuse of cocaine and alcohol - the general was a rare combination of an alcoholic and a drug addict in one person. S. himself did not deny these accusations. In the book "Crimea in 1920" he cited his report to Wrangel on April 5, 1920, where, in particular, he sharply criticized Obolensky and noted that “the struggle is going on with the native defenders of the front, up to and including me, even invading my privacy(alcohol, cocaine)”, i.e., recognizing the presence of these vices, protested only against the fact that they became the property of the general public. Bulgakov reduced the illness of his Khludov, first of all, to the pangs of conscience for the crimes committed and participation in the movement, on the side of which there is no truth.

Obolensky explained S.'s return to Soviet Russia as follows: “Slashchev is a victim of the civil war. From this naturally intelligent, capable, albeit uncultured person, she made a shameless adventurer. Imitating either Suvorov or Napoleon, he dreamed of fame and glory. The cocaine he drugged himself with kept his wild dreams alive. And suddenly, General Slashchev-Krymsky breeds turkeys in Constantinople on a loan received from the Zemsky Union! And then? .. Here ... abroad, his adventurism and insatiable ambition had nowhere to play out. There was a long working life ahead until it would be possible to return home modestly and forgotten ... And there, the Bolsheviks still have a chance to advance, if not to the Napoleons, then to the Suvorovs. And Slashchev went to Moscow, ready in case of need to shed "white" blood in the same amount in which he shed "red".

The memoirist experienced mixed feelings of pity, sympathy, contempt and condemnation for the former persecutor for the transition to the Bolsheviks (it was Obolensky who helped S. acquire a farm on which the former general's working life did not work out). Further, the author of "Crimea under Wrangel" cited a comic story, how in Moscow one former Crimean Menshevik, whom S. almost hanged, having already joined the Bolshevik Party and working in a Soviet institution, met the red commander of "comrade" S., and how they peacefully remembered the past. Perhaps this is where Charnota's humorous remark was born in Bega, that he would have signed up with the Bolsheviks for a day, just to deal with Korzukhin, and then he would have immediately "discharged". Bulgakov probably remembered S.'s words cited by Furmanov about his readiness to fight in the ranks of the Red Army, confirming Obolensky's thought, and he hardly doubted career and worldly, rather than spiritual and ideological reasons for the return of the former general. Therefore, Khludov had to endow the pangs of conscience of the autobiographical hero of the Red Crown, in whose insane mind the image of his dead brother is constantly present.

In addition to Obolensky's memoirs, the playwright took into account other testimonies about S. He was familiar with the book of the former head of the press department in the Crimean government, G. V. Nemirovich-Danchenko, “In the Crimea under Wrangel. Facts and Results”, published in Berlin in 1922. It, in particular, noted: “The front held on thanks to the courage of a handful of junkers and the personal courage of such a gambler as the gene was. Slashchev. And G. N. Rakovsky wrote the following about S.: “Slashchev, in essence, was the self-made dictator of the Crimea and autocratically disposed of both at the front and in the rear ... The local community was driven underground by him, the workers shrank, only "Circles (i.e., the press of Osvag (Information Agency), the press department of the Denikin government. - B.S.) composed enthusiastic praises for the general, popular among the troops. Slashchev fought very vigorously against the Bolsheviks, not only at the front, but also in the rear. Court-martial and execution - that is the punishment that was most often applied to the Bolsheviks and their sympathizers.

The figure of S. turned out to be so bright, contradictory, rich in a variety of colors that in "Running" she served as a prototype not only for General Khludov, but also for two other characters representing the white camp - the Kuban Cossack general Grigory Lukyanovich Charnota ("descendant of the Cossacks") and the hussar colonel Marquis de Brizar. The latter probably owes his surname and title to two more historical figures. The actor playing de Brizar, according to Bulgakov, "does not need to be afraid to give Brizar the epithets: hangman and murderer." This hero shows sadistic inclinations, and as a result of a wound in the head, he is somewhat damaged in his mind. The Marquis de Brizard brings to mind the famous writer Marquis (Count) Donatien Alphonse Francois de Sade (1740-1814), from whose name the very word "sadism" comes. Another prototype of de Brizar was the editor of the Donskoy Vestnik newspaper, the centurion Count Du-Chail, whom Wrangel accused, along with generals V. I. Sidorin (1882-1943) and A. K. Kelchevsky (1869-1923), who commanded the Don Corps , in the Don separatism and betrayed to a court-martial. (During his arrest, Du-Chail tried to shoot himself and was seriously wounded in the head. Subsequently, the court acquitted him, and Du-Chail emigrated.) This case was described by G. V. Nemirovich-Danchenko and other memoirists. From Du-Chail, de Brizard has a French surname, a high-profile title and a severe wound in the head. From S., this character has a luxurious hussar costume and executionerism, as well as clouding of reason, which Khludov also has, but for the Marquis it is a consequence of a wound, and not a split personality and pangs of conscience.

Charnota from S. has a Kuban past (Bulgakov took into account that S. first commanded the Kuban units) and the marching wife Lyuska, the prototype of which was S.'s second wife - "Cossack Varinka", "Nechvolodov's orderly", who accompanied him in all battles and campaigns , twice wounded and more than once saved her husband's life. Some memoirists call her Lidka, although in fact S.'s second wife was called Nina Nikolaevna. From S., Charnota also has the qualities of a gambler, combined with military abilities and a penchant for drunkenness. The fate of Grigory Lukyanovich is a variant of S.'s fate, told by Obolensky, the variant that would have been realized if the general had remained a simple farmer in exile. Then S. could only hope for random luck in the game, but for returning to Russia after many years, if they forget about him there. Charnota, in the course of action, reveals in Khludov's fate some moments inherent in the fate of S. According to Obolensky, people who knew S. before the revolution as a quiet, thoughtful officer were amazed at the change brought about by the civil war, which turned him into a cruel executioner. At the first meeting with Khludov, Charnot, who previously knew Roman Valeryanovich, is amazed at the cruelty manifested in him. And in the finale, commenting on the upcoming return of Khludov, the “descendant of the Cossacks” suggests: “Do you, the General Staff of Lieutenant General, maybe a new cunning plan has matured?” It fully coincides with the real actions of S., who carefully planned his return to Russia, having held lengthy negotiations with Soviet representatives and negotiated for himself forgiveness and work in his specialty. These words of Charnota leave the impression that Khludov in Soviet Russia will not necessarily be executed. However, Bulgakov, in the image of Khludov, is more inclined to the motif of a redemptive sacrifice, so other words of Charnota about what awaits the repentant in his homeland are more memorable:

“You will live, Roma, exactly as long as you need to be removed from the train and brought to the nearest wall, and even then under the strictest guard!”

At the time of the capture of Perekop by the Reds, S. was out of work. Bulgakov's hero commands the front and actually performs a number of functions of generals A.P. Kutepov and P.N. Wrangel. For example, it is Khludov who orders which formations to go to which ports for evacuation. In the books of S. there is no such order given by Wrangel, but it is in other sources, in particular, in the collection “ Last days Crimea". At the same time, Bulgakov makes Khludov criticize the Commander-in-Chief with almost the same words as S. in the book “Crimea in 1920.” criticized Wrangel. So, Khludov’s words: “... But Frunze did not want to portray the designated enemy during the maneuvers ... This is not chess and not the unforgettable Tsarskoe Selo ...” go back to S.’s statement about the fallacy of Wrangel’s decision to start transferring units between Chongar and Perekop the day before Soviet offensive: “... Castling has begun (it works well only in chess). The Reds did not want to portray the designated enemy and attacked the isthmus. The phrase thrown by Khludov to the Commander-in-Chief about the latter’s intention to move to the Kist hotel, and from there to the ship: “Closer to the water?” Is an evil allusion to the cowardice of the commander-in-chief mentioned in the book “Crimea in 1920”: “The evacuation proceeded in a nightmarish environment of confusion and panic. Wrangel was the first to set an example of this, he moved from his house to the Kist hotel near the Grafskaya pier in order to be able to quickly board the ship, which he soon did, starting cruising through the ports under the guise of checking evacuation. Of course, he could not do any verification from the ship, but he was in complete safety, and this was the only thing he aspired to.

In the later editions of The Run, where Khludov committed suicide, he spoke ironically and allegorically about his intention to return to Russia as about an upcoming trip to a German sanatorium for treatment. This meant the story told by S. in his memoirs, how he refused Wrangel's offer to go to a sanatorium in Germany for treatment, not wanting to spend people's money on his person - a scarce currency.

As an antipode to Khludov (S.), Bulgakov gave a reduced caricature image of the white Commander-in-Chief (Wrangel). The words of Archbishop Afrikan, whose prototype was the head of the clergy of the Russian army, Bishop of Sevastopol Veniamin (Ivan Fedchenko) (1881-1961), addressed to the Commander-in-Chief: “Dare, glorious general, light and power are with you, victory and affirmation, dare, for you are Peter, what does a stone mean”, have as their source the memories of G. N. Rakovsky, who noted that “representatives of the militant Black Hundred clergy with Bishop Veniamin, who actively supported Wrangel even when he was fighting Denikin”, from church pulpits “glorified Peter Wrangel , comparing him not only with Peter the Great, but even with the Apostle Peter. He will be, they say, the stone on which the foundation of the new Russia will be built. The comical appeal to Afrikan by the Commander-in-Chief himself: “Your Eminence, abandoned by the Western European powers, deceived by the treacherous Poles, in the most terrible hour we trust in God’s mercy,” parodies Wrangel’s last order when leaving the Crimea:

“Abandoned by the whole world, the bloodless army, which fought not only for our Russian cause, but also for the cause of the whole world, is leaving its native land. We go to a foreign land, we go not like beggars with an outstretched hand, but with our heads held high, in the consciousness of a fulfilled duty. The poverty that befell Khludov, Charnot, Lyuska, Seraphim, Golubkov and other emigrants in "Running" in Constantinople shows the falsity of Wrangel's grandiloquent words.