What is the purpose of the writer talking about it? The most amazing rural school in Russia. History of Dmitrievskaya secondary school

Sergey Alexandrovich Rachinsky was born on May 2 (14), 1833 in an old noble family of Rachinsky-Baratynsky, in a family estate in the village. Tatev, Belsky district, Smolensk province (now Oleninsky district, Tver region).

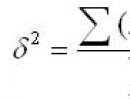

Having received an excellent home education, in 1849 he entered Moscow University. His sphere scientific interests became botany, plant physiology. In 1866 he defended his doctoral dissertation "On some chemical transformations of plant tissues". But his interests were not limited to the natural sciences. Rachinsky is actively engaged in philosophy, as well as social and teaching activities. As a man of encyclopedic knowledge, he had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances. He communicated with philosophers A.S. Khomyakov, brothers Kireevsky, V.V. Rozanov, S.M. Solovyov, was friends with V.P. Botkin and the zoologist K.F. steering wheel. The welcome guests in Rachinsky's house in Moscow were: L.N. Tolstoy, P.I. Tchaikovsky, Aksakov brothers, historian V.I. Guerrier and many others.

Having retired from the post of professor at Moscow University in 1868, S.A. Rachinsky settled in his family estate Tatev. Here he founded a school and 18 more schools in the district, which formed a kind of educational and educational space. A community of educators emerged, united by one idea and one leader. The influence of S.A. Rachinsky and the schools he created on the school business turned out to be so significant that the debate about his role in domestic pedagogy has not subsided to this day. The key to understanding the whole pedagogical concept of this scientist and practical teacher is, according to the researchers, that in

The basis of his school was family education, the traditions of Russian folk life and its Orthodox foundations.

Despite the fact that Rachinsky's schools achieved brilliant results, many teachers of the late 19th - early 20th centuries and modern scientists attributed S.A. Rachinsky to the apologists of the parochial school. He was even called a "terry reactionary."

Meanwhile, Rachinsky saw in religion, first of all, the basis of the spirituality of the child in the conditions of his time. In the ministers of the church in the conditions of the then village, he saw the most prepared teachers and noticed that "the people themselves recognize the clergy as their teacher."

The main distinguishing feature of the rural school, according to Rachinsky, is that it is primarily an institution educational. The Rachinsky school was dominated by the spirit of folk culture, the traditions of the rural community. His school can be called the school of "good morals". Her curriculum had an artistic and aesthetic focus. Life at school was based on creative work, games and holidays played an important role.

S.A. Schools Rachinsky - institutions of their time. The organization of the educational process in them took into account the interests of parents and the peculiarities of peasant life. In his school, they taught the culture of agriculture, beekeeping and gardening, the basics of carpentry and joinery, and introduced them to folk crafts. The main didactic task was to instill skills in students. At the same time, such a methodological technique was used as independent educational work of students with the help and under the guidance of a teacher. Rachinsky's educational system was based on three fundamental ideas: humanism, nationality and morality.

If we apply modern concepts of the theory of educational systems, then the educational system of Rachinsky, implemented by him in the Tatev school and a number of other rural schools in the Tver and Smolensk provinces, can be characterized through a set of components.

The first component of the educational system is the goals of education and the tasks of the school arising from them.

The goals of education, according to Rachinsky:

The development of the mental powers of the child;

Development of his will;

Harmonious development of the pupil's mental strength, heart, feelings and higher spiritual gifts;

Creation of a morally integral character. The Rachinsky schools set themselves the following tasks:

Teaching children for later life;

To cultivate a sense of duty and benevolence, friendship and tenderness;

To develop firmness, steadfastness, self-control, to strengthen pupils for the struggle of life.

Rachinsky's schools cultivated an individual approach to teaching and upbringing. The teacher was responsible for the upbringing in the class - a class mentor.

The nature of relationships in Rachinsky's school was family. The first condition for successful education was considered friendly relations with students. A teacher in the schools of Rachinsky for the first time in Russian education was assigned the role of an older friend. Professional requirements for a teacher were formed from love for the cause of education and knowledge of the subject. Schools prepared teachers for themselves from the most gifted of their students.

Such principles and forms of education were recognized as effective, such as:

Great freedom in everything that does not carry evil in itself;

Resolving conflicts within the team;

A variety of hobby activities during free hours;

Annual cycle of school celebrations, holidays.

Rachinsky's school actively explored the environment. This was expressed in her participation in all rural events. It was recognized as necessary to use all the forces ready to come to the aid of the upbringing and education of children.

The teachers of the Rachinsky schools acted as a community in which there was an exchange of experience and learning took place. Such meetings were held in Tatev and attracted teachers, many educated people not only from schools in the area, but also from other places in Russia.

In some schools of Rachinsky, self-management was introduced in the form of school councils, which were endowed with broad powers. They were composed of a chairman, a trustee, teachers, and elected representatives from the ward. The school councils had financial resources and actually determined the state and development of schools.

Thus, upbringing was placed "at the forefront" in the rural school of Rachinsky. The main thing in the school was her spirit.

The educational task of the school was to develop in children those spiritual treasures with which the soul of the Russian people is rich.

The researchers of that time left us their understanding of the pedagogical views of S.A. Rachinsky and the structure of his school.

Life in the Tatev school was built in accordance with the people's character and way of life. "S.A. Rachinsky thought deeply about every detail, every little thing, both in the external environment of his school, and in the order of classes, in the way of life and in mutual relations with his children, and all members of the school family among themselves. The school was striking in its cleanliness S.A. Rachinsky managed to give his school a beautiful and artistic look ... almost exclusively by the students themselves. " The school taught children to work and brought up a love for peasant work and crafts. The pupils did everything around the house: they stoked the stoves, carried water, washed the floors, cleaned and cleaned the school, helped the cook, guarded.

The usual school system of life was decorated with a number of school celebrations. The ingenious teacher eliminated one important shortcoming of our school - inattention to children from the school in holidays. He even said that the school should be remembered not by weekdays, but by holidays.

Rachinsky for the first time in pedagogical practice applied the folk way of educating patriotism - traveling to Russian holy places. For the first time, he managed to show more fully, brighter, more clearly and more convincingly than anyone what the people are looking for in school and what they should give the Russian people.

rural elementary school.

Our knowledge of the Rachinsky school is supplemented by the pedagogical articles of V-Lyaskovsky, who corresponded with Sergei Alexandrovich for 20 years and visited Tatevo more than once. From his first visit, he made many interesting judgments about what he saw and heard. One of them: "The head of these schools, through long experience, came to the conclusion that it is not knowledge that is firmly instilled in children, but skills." Second observation: “The requirements for teaching by the parents of students ... are essentially purely practical in nature. Not education or development in general ... a peasant is looking for his son, sending him to school, but the same simple and uncomplicated skills .. .". S.A. Rachinsky "was the first to dare to say directly that the school must comply with the requirements placed on it by the parents of students, even if they are illiterate." Meanwhile, everywhere "elementary school in Russia was conducted on the model of foreign schools; it was, firstly, a completely secular school and, secondly, its program was not at all in line with the demands of Russian people's life."

An important feature is that "almost all the teachers teaching in the schools of Sergei Alexandrovich are the pupils of these same schools" (Rachinsky trained more than 50 teachers).

In the village of Glukhovo, 12 versts from Tatev, the candidate of literature N.M. Gorbov. He outlined his theory of education in the work "On external methods of education in a public school", where he also used the views of S.A. Rachinsky. N.M. Gorbov defines education as follows: "It is a concern for the development of good skills in students, mental, moral, physical." N.M. Gorbov believed that "the power of education" should be primarily an internal force. To "external methods of education" he refers to coercive measures: rewards and punishments. They recognize the practical meaning of rewards for academic excellence; rewards for good behavior, in his opinion, are harmful, and it is impossible to build a system of education on punishments.

The modern theory of educational systems can include in its arsenal the passionate appeal of N.M. Gorbov, addressed by him to the teachers of the early 20th century: "O teacher! Come down from your impregnable pulpit, leave your pitiful, ridiculous greatness on it, approach your students as a friend and tell them:" Let's work together.

These are other statements of the scientist, rural teacher and student S.A. Rachinsky perfectly reflect the essence of the ideas about building relationships in a rural school that existed in the schools of Rachinsky: "Cheerful independent work of students with the help and under the guidance of a close friend of the teacher, this is the picture that ... the school you must not bridle your disciples and not fight with them, but live with them in the loving communion of truth and goodness.

Paying tribute to the role of the school in the upbringing of children, nevertheless N.M. Gorbov argued that "the natural place of education is in the family. The school is the family's helper."

The Tatev school has been a "mental center" for over 17 years. Here, special views on the school program and teaching methods were formed. Rachinsky demanded from teachers, first of all, knowledge of the subject, the goals of teaching, and believed that "the simpler they teach, the better - if only they taught diligently." An important place was given to literature and mathematics. Rachinsky argued that literacy itself is "a means in the struggle of life." Scientific knowledge should be supplemented with various practical knowledge and skills. But, as already emphasized, the distinctive feature of his program - or the structure of the Tatev school - was its educational side.

Rachinsky's theory of upbringing is vividly characterized and revealed in the diary of the teacher of the Drovna school, a student of Sergei Alexandrovich, V. Lebedev. This school, located in Drovnino, Gzhatsk district, Smolensk province (neighboring district with Belsky), crafts flourished.

A school with a two-year course of study was opened in 1886, there were 40 students. After 7 years,

200 children were trained. The course of study became six years. It was extended and had a general educational character. At the end of the course, the pupils were divided into the following groups: leaving school, artisans, and those striving for teaching.

Based on their observations, the teachers of the Drovna school considered it necessary to entrust the management of each school to a council consisting of a chairman-priest, teachers, a trustee, and elected representatives from the parish. The council could "reduce and expand the program, transfer from one year to another the provisions of the program, draw up and change the schedule of lessons, establish the order of the day at school, set the dates for the admission of students, the beginning and end of the academic year, transfer from one department to another without exams , dismiss a student, set out the conditions for accepting students in a hostel, choose textbooks and manuals, ... look for teachers ... ".

Observation of the daily course of school life passed through the duty of all teachers.

Much attention was paid to the correct setting of the workshops. The teachers of the Drovna school believed that in the conditions of a rural school "one cannot learn a craft, one can only get acquainted with it." In order to "introduce handicraft knowledge, especially applicable to agriculture, into the peasant environment, and to keep more students at school, and to weaken the harmful influence of the capital's workshops," the teaching of the craft at the school was structured as follows: the students were taught the skill by the master; the teacher watched and guided the master; the teacher, head of the workshop, had to have sufficient special knowledge (you should never trust one master); the main goal for apprentices in the workshops is to learn the craft; sciences and crafts cannot exist at the same time and equally in school.

In the schools of Rachinsky, agricultural work, familiarization with the culture of agriculture "becomes an almost general educational subject."

Clearly realizing that "education designed exclusively for the narrow sphere of local temporary

needs, drowns out the innate ability of a person to develop, "S.A. Rachinsky is looking for answers to the questions he himself posed. Where is the middle way between such extremes as the development of the child's personality and the specific needs of society? To what extent should education be national and modern, to what Rachinsky considered another eternal problem of education to be developed in him? , individualism can develop to a dangerous level for society.Is there and where is it, "a true, legitimate limit to this striving, where are the means to keep its development within the proper limits, without violating the nature of the child"?

V.V. Rozanov, who knew Sergei Alexandrovich well, spoke of Rachinsky as follows: “He was never only a specialist ... The circle of his mental and heart interests was infinitely and indefinitely diverse. He was a philosopher in his life's work, especially in practical philosophy, expressed in business."

His pedagogical ideas S.A. Rachinsky outlined in the collection of articles "Rural School". The book was published in 1891, 1892, 1898, 1899, 1902 and 1991. At one time, it was a reference book for the teaching staff of Russia and can truly be called a school testament for the Russian folk school.

SCHOOL E.S. LEVITSKY IN TSARSKOYE Selo: THE EXPERIENCE OF CREATING "NEW SCHOOLS" IN RUSSIA

AT late XIX centuries, the so-called new schools arose in the West. They differed from each other in their conceptual attitudes, content of education, forms and methods of teaching and learning.

nutritional work. Flo, despite all the diversity, one feature was inherent in this movement - a negative attitude towards traditional pedagogy. Representatives of the "new upbringing" put the child's personality, its originality, at the center of education and upbringing. Moreover, decisive importance in the development of the child's personality was given to his own experience.

The "new schools" were located mainly outside the city, such as, for example, the Waldorf schools. These were private educational establishments, which also distinguished them from the classical gymnasium. The boys studied here together with the girls. The teacher tried to introduce children to different cultures, different values.

At the turn of the new, 20th century, several "new schools" also appeared in Russia. This is the school of E.S. Levitskaya in Tsarskoye Selo (1900), gymnasium E.D. Petrova in Novocherkassk (1906) and O.N. Yakovleva in Golitsyn near Moscow (1910). Carrying out education close to nature, caring for the harmonious development of children's strengths, paying great attention to physical education and hygienic conditions for the life and work of students, reasonably organizing studying proccess, they, like other "new schools", set as their goal the education of knowledgeable, strong-willed, enterprising figures capable of becoming leaders of the economy, "captains of industry", in which developing capitalism more and more needed. The first of these schools was opened by E.S. Levitskaya (the granddaughter of the famous writer and historian N.A. Polevoy), who herself visited England, and then France and Germany, carefully studied the organization of "new schools" and decided to establish the same in Russia.

Like other educational institutions created by the forces of private and public initiative and departed from the official model, the Levitskaya school had a hard time defending its existence, overcoming various obstacles and prohibitions. It was not possible to create a secondary school with co-education of girls and boys in the then Russian conditions, so at first a small school was organized from the lower grades, in which only six students began classes - three girls and three boys. 34

A year and a half later, in order to open the third class with co-education and to have the opportunity to accept as boarders not only boys, as was allowed at the beginning, but also girls, it was necessary to seek special permission from the Minister of Public Education; a petition to open the next class had to be submitted each year. Minister Vannovsky, in turn, addressed a special report to the tsar and only thanks to the "highest mercy", or rather thanks to the energy and perseverance of E.S. The Levitskaya school could develop into a secondary educational institution. The decisive role was also played by the fact that the Levitskaya institution was a small and very expensive school for the children of rich and noble parents. These restrictive conditions of the school were also emphasized by the trustee of the educational district, who reported that coeducation was allowed here for a very limited number of students "from good families(because the fees are very high)."

The reputation of the educational institution in the eyes of the authorities was strengthened by the fact that in the troubled years of 1905-1907. this school, the only one of the Tsarskoye Selo educational institutions, was not affected by student riots. Classes at the school were not interrupted for a single day, and in June 1907 she received the rights of government men's gymnasiums. The first graduation from the school took place in December 1908. In the eighth graduating class, there were only four graduates who showed brilliant knowledge in the entire course in the exams.

The entire educational system of the Levitskaya educational institution was focused on achieving the goals set " new school". It was considered very important to give the school a homely, family character, so that there would not be the slightest hint of bureaucracy and formalism, and all kinds of interesting work, games, excursions and conversations would take the place of boring book studies and cramming. For this, according to Levitskaya's firm conviction, the school should have 80-100 pupils (no more than 15 students per class).A rich aristocratic school could, of course, afford such a luxury.In the 1915/16 academic year, for example, there were 46 students and 34 teachers in eight classes of the school.

The teacher, who was entrusted with 10-15 children, was at the same time their teacher. Living with the pupils, taking part in all their activities, games and amusements, he knew perfectly well all the individual characteristics and character traits of each child. The educational influence of the teacher played a huge role.

With all the homely, family nature of the school, Levitskaya ensured that a businesslike atmosphere reigned there, a clear, strict and even harsh regime. A firm daily routine was strictly observed, constant monitoring of the clear and mandatory implementation of all the rules and orders given to both children and educators, strictness and smartness in clothes and in all the appearance of adults and children. The authority of the boss was very high. The secret of the school's success was seen by many in its "intolerance, amounting to fanaticism, to any form of physical and moral slovenliness." Levitskaya did not tolerate slovenliness either in clothes, or in gait, or in work. Firm discipline and diligence at school were achieved not only by persuasion, but also by such measures as deprivation of vacation, participation in a common holiday, etc. There was also a punishment cell.

From the very first days of being at school, children were taught to be independent. In everything necessary, they were obliged to serve themselves: make beds, keep shoes, clothes and personal belongings in order. Later, they were given various assignments: duty in the classroom, in the dining room, at the telephone, managing sports equipment, teaching aids, receiving and sending mail, etc. In the absence of the boss, educator, minister (the time of their rest was considered sacred, and no one had the right to disturb them during these hours, even on urgent business), the pupils completely replaced them.

Senior pupils were allowed independent, unaccompanied trips home, on vacation, they were sent on assignments to St. Petersburg, they were appointed treasurers of any amounts for school expenses or custodians of students' pocket money. The presence of pocket money was considered one of the educational measures. Children were taught prudently, economically, prudently to spend the money received from their parents (for travel, postage, etc.).

other expenses), in addition, pupils were obliged to compensate for damage to school things from their personal money. Such an unforeseen expense or uneconomical, wasteful spending of pocket money could deprive the pupil of vacation if he had no money left for travel.

The school knew that it educates those who, in time, will themselves become the masters and managers of a large house, business, service, therefore, it paid great attention to the development of business qualities, composure, organization, prudence and persistently accustomed to unquestioning obedience to the established order.

One of the main tasks of moral education in the Levitskaya school was considered the education of the will. To overcome irritability during a quarrel, to refrain, for example, from the desire to get drunk when thirsty, was recognized as a great valor. Any manifestation of weakness, lack of will was condemned and became the subject of a special conversation.

A large role was assigned to the education of the traits of a "gentleman". The children were constantly taught that the willing and gracious fulfillment of a request, an order, the provision of a service to others is required in a hostel from every educated person. Rudeness, boasting, injustice to each other in the relations of children were eradicated. Sneaking was condemned, the boss and teachers did not accept complaints about comrades. What was transmitted by someone was not understood. But such offenses as lies, deceit, cunning, malice towards comrades, deliberate disrespect for school rules, were referred to a comrades' court. The decision of the court was communicated to the boss, who could either approve or not approve it. The latter happened very rarely. The court played an important role in school self-government, which was seen as a means of educating independence, responsibility for one's actions, developing public opinion and moral criteria.

An important place in the life of the school was occupied by school clubs that united peer students. Their work was organized by the students themselves; educators acted only in the appropriate role, they could be invited

Sheny to participate in debates, discussion of essays prepared by students, in literary and scientific readings and other club activities.

The school paid special attention to the physical health of pupils, believing that without this it is impossible to successfully solve any other educational tasks. Like most of the "new schools", Levitskaya's educational institution was located in a beautiful countryside. Services, farms with their own cows, a garden, a vegetable garden, football grounds, lawn tennis, and a skating rink were located on 50 acres of land. 36 acres occupied a large field for games, walks, and celebrations. Convenience, simplicity, perfect cleanliness, many colors, an abundance of light and air should have a beneficial effect not only on the physical condition, but also on the general mood of children, maintaining vigor and cheerfulness in them, educating them aesthetically. All rooms, especially the bedrooms, were thoroughly ventilated, and the temperature was kept fairly low.

A lot of time was devoted to physical exercises, outdoor games, sports: in winter - skating, skiing, hockey, arranging an ice slide, snow removal; in summer and spring - football, croquet, tennis, bast shoes, work in the garden and garden. Between lessons, 20-minute gymnastics classes were held, most often outdoors, to the music. In any weather, every morning for all the pupils began with a run and pouring or wiping with cold water.

Three times a week a special military teacher conducted drill exercises, the rest of the time gymnastics, running, exercises on the uneven bars and other shells were led by an English teacher. The physical education of beginners and weakened children was individualized. It was considered useful for high school students to tire out with gymnastics before going to bed, which was done every other day. Every spring, big sports festivals were held, where children demonstrated their skills and achievements.

In the field of mental education, the Levitskaya school basically followed the same principles as the others.

"new schools". And although, in determining the content of education, she could not ignore the compulsory program established by the ministry for gymnasiums, the school tried to fill the gaps in the program by deepening the course of individual subjects and including English and other additional disciplines. The expansion of the program complicated the educational process, therefore, in order to avoid overload, the teaching methodology, the well-thought-out organization of classes, and the daily routine became important. The conditions of the boarding school made it possible to rationally plan teaching load during the whole day.

Recognizing the importance of accustoming children to independent work, the school created the necessary conditions for classes outside of school hours: pupils could conduct experiments, collect collections, herbariums, make crafts, do needlework, prepare essays and reports, refer to literary sources. Weekly popular science lectures on chemistry, astronomy, art history were held at the school, accompanied by all kinds of illustrations. The students themselves played an active role in their organization.

School teachers, testing new methods developed by pedagogical science on the basis of experimental psychology research, developed their own methods and methods of teaching aimed at activating the educational process, awakening and developing interest in learning, independent thinking of students.

Much attention was paid to the ability to practically apply the acquired knowledge in labor lessons, in school workshops, during field and garden work. As in foreign "new schools", physical labor was considered here as a factor in strengthening health, developing physical dexterity, quick wits, and curiosity.

A similar educational system was created in other Russian "new schools". Organizing their work on the basis of the latest achievements of pedagogical science, instilling in children "gentleman's" concepts of honor, endurance, nobility, instilling the habit of self-service, introducing elements of student sa-39

management, tempering the body, developing the intellect and artistic taste of the pupils, these schools contributed to the formation of the elite of the then Russian society.

SUMMERHILL SCHOOL - FREE EDUCATION SYSTEM

Summerhill School was founded in 1921 in Leiston (Suffolk), about a hundred miles from London (from 1921 to 1924 it was in Germany). The founder of this school is the English teacher Alexander Neill (1883-1973). As the commission of the British Ministry of Education wrote about Summerhill, "this school is known throughout the world as a place where pedagogical experiment is carried out in a revolutionary way and where the published, widely known and debated views of its headmaster are brought to life."

Summerhill is a boarding school that was housed in four buildings surrounded by a green area designed for outdoor play. Children lived according to age groups together with a teacher (a house-mother). The main building contained a dining room, a hall, a modeling workshop, a small room for needlework and a bedroom for girls. The youngest children had a separate house with living quarters and a classroom. The boys' dormitory, the rest of the classrooms, and the rooms of some members of the staff were also located in the cabins. Both boys and girls lived in double or quadruple rooms. Only a few older children lived separately. Classes were small but sufficient for group learning. Housing conditions were generally not the best, however, as emphasized in the report of the inspectors of the Ministry, the children felt well and did not get sick.

The financial situation of the school was very difficult, since it was actually outside the national education system and received meager subsidies from the ministry. To school at -40

They took mostly children from the middle strata of society. Neill was careful not to take children to wealthy families, as he believed that it was difficult to get to the essence of a child if it was hidden behind a lot of money and expensive clothes. In an effort to enroll children from the poorest sections of society, Neill set very low fees for the stay of children in Summerhill. The result was constant financial difficulties, very low salaries for teachers. Evil tongues claimed that because of the low pay in Summerhill, only desperate people, "fliers" or rich idealists could work and worked.

At first, Neill's school was mostly attended by children who had problems in the family and school. Their parents sent them to Summerhill for re-education and re-socialization, after which they were returned to a regular school. Thus, Summerhill performed a rehabilitation function in relation to such children. Over time, the situation changed, and the school began to accept children whose parents believed in Summerhill's idea.

In the early years, there were few girls here, usually only those who had difficulty in the then girls' school were brought here. Later, there were more girls, although their school dropout rate was higher than that of boys. Neill explained this by the financial difficulties of his parents, who, according to a long tradition, preferred to invest in the education of their sons. The school accepted children from 5 to 15-16 years old (Neill noted that he would prefer to recruit seven-year-olds). The total number in different time ranged from 45 to 75 people. Children were divided into three age groups: 5-7 years old, 8-10 years old, 11-15-16 years old.

The staff at Summerhill was sufficient to keep the children out of self-service work. So, in 1964, there were 25 staff members for 75 children, of which two were teachers.

Neill carefully selected the teachers, paying special attention to the fact that, in addition to professional qualifications, they had a sense of humor, a developed sense of community, character traits that made it possible to adapt to the Summerhill system. Very often by test, from 41

which depended on the teacher's employment was the answer to the question: "How will you react if a child calls you a complete fool?" Neill favored those candidates who knew how to do something with their hands, did not shy away from physical work and could fix a rickety door or patch a hole in the wall.

The main responsibility of teachers was teaching. Guardianship of children in residential premises was carried out by educators. Nevertheless, teachers voluntarily organized extracurricular activities for children: they played, prepared performances, and helped with homework. "The teacher runs lessons from 9.30 to 13.15... after which he can, if he wants, spend the rest of the day in bed. Only no one does this, because they have a developed sense of community and they also want to take an active part in society."

A typical day at school went like this. Between 8.15 and 9.00 breakfast, until 9.30 - bedding. Classes started at 9:30 and continued until 13:00.

The lesson plan was given to teachers at the beginning of each semester. Lessons, as a rule, were built according to the age of the children. Usually children studied five lessons a day, each for forty minutes. Lessons were always held in a certain place and at a certain time. Preschoolers and younger students had lunch at 12.30, and staff and older children at 13.30.

The younger children from 7 to 9 years old studied with one teacher, who conducted classes not only in the classroom, but also in the workshop of technical creativity or the art room.

The afternoon was free. The kids did what they wanted. Some played gangsters and policemen, others organized sports games, others listened to the radio, painted, painted, rode a bicycle, worked in workshops and made boats, toy guns or repaired bicycles.

At sixteen o'clock - afternoon tea. At 17:00 various classes began. The younger ones usually read fairy tales. The middle-aged guys loved to work in the art room, where they painted, made pictures from linoleum, leather goods, prepared costumes for their spec-42

takley, wove baskets and sculpted pots. The elders spent a lot of time in the locksmith and carpentry workshops. Children always decide what to do with them. Educators could advise, but never offered a ready-made program of action.

Evenings at Summerhill, however, had a certain routine. So, on Monday the children went to the cinema, on Tuesday the staff and older pupils listened to Neill's lectures on psychology, while the younger ones were busy reading at that time. Dance evenings were held on Wednesdays. Thursday evening was not busy with anything, and the elders often went to the cinema. Theatrical performances were staged on Friday. Saturday was a very important day: the weekly meetings were held on this day school government- School meetings. Then dances, and in winter - theatrical performances. Sometimes on Saturdays, Neill would tell the children about his imaginary journeys through Africa, under the ocean, or in the heavens above the clouds.

The life of the Summerhill school, at first glance, was no different from ordinary schools in Western Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Unless its location in the bosom of nature and the presence of self-government institutions make it possible to assume that it belonged to the so-called "new schools". However, if you look at Summerhill from the point of view of its concept and nature of life, you can see that it really was an unusual school. Alexander Neill was a principled opponent of authoritarian education, moreover, he believed that the future of mankind fully depends on what kind of educators come to children. If these are supporters of a rigid pedagogy of suppression, then humanity will never be able to free itself from wars and crimes. Hatred always breeds hatred. "The only road is the road of love."

In creating Summerhill, Neill consciously contrasted the concept of his school with an emphasis on regime, discipline and coercion. As Neill noted, when founding the school, he pursued one single

the goal is the happiness of the child, and he saw the main path in adapting the school to the child, and not the child to the school.

The concept of the Summerhill school was based on the belief that the child is inherently good and only society and upbringing spoil him. "Fourty years practical work not only did they not reduce this belief, but even strengthened it," Neill wrote later. Recognizing the unreality of attempts to globally reform society, Neill deliberately chose a different path: the organization of a closed children's institution that creates conditions for the free development of the child.

One of the American professors who visited Summerhill criticized the school for being an isolated island in the surrounding society and, in fact, opposing itself to this society. Neill, on the other hand, believed that it was impossible to organize a free school even in a small town, all the more making it part of municipal life, since in this environment there will always be those who do not accept the ideas of freedom, and then it would be necessary to compromise. Neill did not consider it possible to change one iota of his key idea. He agreed that Summerhill was indeed an island (although Summerhillers had many friendly contacts with the people of Leiston). Reflecting on the accusation, Neill assumed that his American colleague meant that, isolated from society, the Summerhill system could in no way contribute to changing the unjust and inharmonious world surrounding the child, and that it could not do anything about the abyss which lies between adults and children. Neill replied that although he believed in the need to change society, nevertheless, his goal was to ensure the happiness of at least a small number of children.

The traditional school, which adapts the child to the ideas of adults about what he should be, does not guarantee him happiness. By imposing their own pace and methods of learning, with early years entangling a child in a network of orders and prohibitions, limiting his natural development, adults unconsciously ignore the child's right to be himself, the right to play, creativity and childhood. 44

Refusing from the outset any teachings, suggestions and statements of a moral and religious nature, Summerhill's educators gave the children the right to be themselves.

Neill argued that every child has a unique personality, the ability to love life and find their own interest in it. If left to himself, he will develop according to his individual inclinations. It is only necessary to give him absolute freedom. A child whose life is not constantly controlled by adults, sooner or later achieves success in life. Thus, the main principle of Summerhill's life was freedom.

The former school was aimed mainly at the intellectual development of students. Neill believed that the emotional life is much more important than the intellectual. He was convinced that it was better to raise a happy janitor than a neurotic scientist. Considering that the ever-deepening gap between reason and feeling became the tragedy of the era, Neill dreamed of removing the burden of awareness of original sin, restoring faith in good human nature, and making the child perceive the world calmly and joyfully. The main task of the school, therefore, is to provide the child with the opportunity to live his own life, and not the life imposed on him by parents or teachers in accordance with their educational goals. Such management of a child's life, according to Neill, gives rise to obedient robots, and this is dangerous for the development of civilization.

Being convinced that feelings are inextricably linked with an active life position, with creativity, that they have a positive effect on mental development, Neill created the opportunity for free self-discovery for children in Summerhill. He discarded all the conventions of society, rules and prohibitions, leaving the only rule governing the behavior of children, mutual respect for feelings. The child could behave in any way, as long as it did not hurt the feelings of another person or harm him.

Neill was convinced that Summerhill was the happiest school in the world. The proof of this is the absence of those who are very homesick, the rarely occurring fights and the fact that you will not hear children crying here. He saw the reason primarily in the fact that free children do not hate their environment, as is often the case in authoritarian schools. Because hate breeds hate, and love breeds love. For Neill, loving a child is total acceptance. You cannot be on the side of the child if you punish him and do not trust him. And in Summerhill, the children knew they were accepted for who they were.

In addition, Neill assigned Summerhill a therapeutic function in relation to those children who came to his school already a little "spoiled", that is, full of hate and aggression complexes, which was the result of the negative impact of the family and school. In such cases, he set the task for educators to surround these children with special care so that they feel safe, understand that nothing threatens them, that they are accepted and loved. For many years, Neill gave individual "treatment" at Summerhill, but over time he realized that he could do without it. Years of observation of children's behavior convinced him that the very situation of freedom in Summerhill had a healing effect.

Children had the opportunity to freely express themselves through dance, music, drawing, painting, theater, outdoor movements, which naturally released their emotions and helped them find the most suitable form of manifestation. Being in a system of democratic interpersonal relations, surrounded by cordial, but not petty care, children quickly got rid of fear of adults, matured spiritually and found joy and interest in life.

The relationship between adults and children is a matter of particular importance. In Summerhill, adults and children were equal in everything that concerned rights and duties. Naturally, it was not about the responsibility for the life and health of children. Both adults and children addressed each other by their first names (the only exception was Mrs. Neill, by 46

which the children addressed by their surnames). It was difficult for outsiders to distinguish where the cooks, gardeners and tutors were. The attitude of the staff towards the children was characterized by immediacy and cooperation. Children did not feel fear or alienation towards adults and went to them with all their problems. Even if someone was to blame, they were not afraid to admit it themselves.

Another important principle of Neill's pedagogical system was the principle of self-regulation. Neill believed that the life of a child could well be built on self-regulation. Therefore, one should not strive to form the child's skills or to manage his choice. Self-regulation means the child's right to a free life, the absence of external power regulating his psyche or the somatic side of his life, since the mechanism of regulation is to some extent "built-in" into the human body. The child has the right to eat when he is hungry, and not when he should according to the regimen. You can not force a child to eat any particular food in a certain amount. If the child has a choice, then he will choose as much food as he needs without anyone's help. It is impossible to impose one or another type of clothing on a child; he himself will perfectly adapt to changes in the weather: if he feels cold, he will dress warmly, when he gets hot, he will take off his sweater.

Neill allowed the children at Summerhill to go to bed whenever they wanted (except when the sleep time was determined by the children themselves by popular vote). He believed that children were guided by common sense and it was in their own interest to get a good night's sleep.

The principle of self-regulation applied to the entire life of society in Summerhill and meant giving children the right to independently solve problems without recourse to the authority and power of adults. For example, when one of the children did not regularly come to class, the group could express their dissatisfaction and ask that a friend either promise to participate in classes or stop going altogether - otherwise he interferes with everyone. If this does not help, you can submit a proposal to punish the guilty person at a meeting of the school government. This is not 47

meant that group pressure replaced the teacher's formal intervention. After all, in Summerhill, children had absolute freedom to attend classes. From this point of view, Summerhill was one of the most liberal schools.

As we can see, the principle of self-regulation in Neill's system was closely intertwined with the principle of freedom. Moreover, they were interdependent and influenced each other. Freedom in Summerhill did not mean anarchy. Indeed, the children could not go to classes, swear, not wash their faces, and even scold the teacher. But it was impossible to take someone else's bicycle without asking, walk on the roof, swim without elders, turn on the light at night when others want to sleep. Freedom does not mean permissiveness. Children were free to do everything that concerned them directly, but they were not allowed to behave in a way that was harmful to their health. In addition, children were to avoid doing things that might hurt the feelings or violate the rights of another person.

Freedom meant that every child or adult has the right to make decisions about himself, but must respect the rights of others and not do anything that would harm another person. For example, a child may break a window in his room, since in this case he himself suffers harm from what he has done. But he has no right to break a window in a room where other people live. If Neill happened to catch a child in some kind of misconduct, then this misconduct was always considered from the point of view of whether it crosses the line beyond which the interests of others begin. In no case were transgressions considered in terms of the usual categories of good and evil. Neill believed that the use of purely moral assessments in this case is unethical, as it gives the child a feeling of guilt, which, in turn, gives rise to fear, hostility and aggressiveness.

The above restrictions separated freedom from anarchy and stemmed from conscious decisions made by children. If, nevertheless, one of the children often violated this code, the children's self-government had a certain system of measures to ensure compliance with the laws of the hostel.

The boundaries of freedom in Summerhill were determined by the norms of social behavior approved by the general meeting of children and adults by voting. This concerned, for example, the lights out for children of different ages, behavior in public places (it was possible to swear in Summerhill, but it was forbidden while walking in the city), prohibitions (children under 11 years old were not allowed to ride a bicycle on their own on the street), activities created children of self-government commissions, inviolability of private property.

Teaching at Summerhill occupied a controversial place, as it was not a priority. As already mentioned, children could not attend classes, it depended only on their desire. There were even children who had not gone to school for years. It is interesting that children who came to Summerhill as preschoolers went to school with a desire and did not drop out of school. The older students, who came to Summerhill from other schools where they had problems, took the freedom of attendance with delight and at first did not think about teaching at all for months. This state, according to Neill, is directly proportional to the level of hatred that the former school laid in them. A kind of record was set by a girl who did not study for three years. The average rate of "recovery" and conversion to the teachings was usually three months.

Often, Neill heard that children living in such conditions would not even lift a finger later to achieve anything, and would later feel their inadequacy in competition with graduates of ordinary schools.

Significant in this regard is the dialogue between Summerhill graduate Jack and the director of one of the machine-building factories:

If you had to start over and you could choose between Eton and Summerhill, which would you choose?

Of course, Summerhill.

What does Summerhill offer that other schools don't?

I think it gives a feeling of absolute self-confidence.

Well, I noticed it as soon as you walked into my office.

I didn't mean to give that impression, I'm sorry.

I liked it. Usually those whom I call to my place are very worried and feel out of place. You entered as a partner.

This dialogue demonstrates the real result of the Summerhill system, where the main thing was not the acquisition of a certain amount of knowledge, but the formation of a desire to know oneself and one's capabilities.

Contrary to predictions, the children who attended the lessons took them seriously and, if for any reason there was no lesson, were very disappointed. Neill recalls a case when, for some offense, he offered to punish a student by excommunicating him from school for a week. The children did not accept this proposal, considering the punishment too harsh.

Neill argued: "Creativity and self-expression are the only things to be considered in education. It doesn't matter what the child does in the creative field: whether he makes tables, whether he cooks oatmeal, whether he makes sketches or sculpts a snowman. More education is to make a snowman than in an hour-long grammar lesson... Making a snowman is closer to real education than the spoon-feeding that today is called education."

Science for science's sake is absurd. It is about the student being able to use knowledge so that the knowledge gained is useful for solving life problems. According to Neill, education is not as important for a child as the development of his personality and character. Science is not equally necessary for everyone. It depends on interests and innate abilities. According to Neill, children, like adults, can only learn something when they themselves want to. child's interests in this case are a kind of life force of the whole personality. Neill saw interests not only as a potential motivator at 50

learning process, but above all as an integral part of human nature, baggage with which a person is born and which he carries through his whole life. Hence Neill's belief that interests cannot be instilled or shaped. Teachers have no right not only to impose something on the child, but even to engage in suggestion. The child must find his calling on his own, find out what interests him, without any help from adults.

Neill constantly reminded of his rule of non-interference in the final choice of the interests and life goals of the pupils. This is evidenced, for example, by the case of thirteen-year-old Venifred, who, after several weeks of absence from school, turned to Neill, expressing her desire to study. He approved of her decision. However, the girl did not know what she would like to learn, and Neill did not give any advice. The problem was not resolved until a few months later, Venifred herself came to the conclusion that she needed to study for the college entrance exams.

Neill consciously sought to ensure that his pupils, without anyone's help, found a goal in life, chose the type of activity that most fully met their inner needs. If this choice concerned teaching, teachers tried their best to give students a good level of knowledge and ensure that they were able to enter higher educational institutions. In general, however, the school was not focused on preparing students for exams. Neill was categorically against all kinds of examinations, and they were arranged only for those who expressed a desire to study further.

A natural consequence of the abandonment of the examination system was the abandonment of the grading system used in traditional schools. Knowledge itself ceased to be a significant indicator, instead, creativity, ingenuity and originality were taken into account.

Neill argued that the task of the school should be to provide children with the opportunity to learn to read,

Other than the innovation of eliminating exams and grades, Neill had no interest in experimenting with teaching methods. He was convinced that it does not matter what method to teach a child to read or divide, one should not invent some new tricks for this. A child who wants to learn something will learn without much innovation in teaching.

Summerhill was a democratic and self-governing school. All issues related to the life of the school or individual groups of children, including those related to punishment for antisocial acts, were usually decided by a general vote on Saturday evening at the school meeting. The only issues that remained within the scope of a sole decision were the hiring and dismissal of teachers (this was done by Neill), as well as the preparation of household orders and accounts (this was done by Neill's wife). According to Neill, participation in the general meeting of the school or school government is of great educational value, often much more than a few reports or lessons, because there children learn to organize their own affairs, responsibility and democracy.

Self-government in Summerhill is the whole team of children and adults. At the beginning of the semester, the local government elects a chairman, who himself appoints the next one a week later. The chairman's role is to conduct the weekly meeting correctly and fairly. The chairman does not replace anyone and has no right to make decisions between self-government meetings. He only conducts meetings, and his role is exclusively auxiliary in relation to the whole society. The same role is played by the secretary, whose functions can be performed by anyone who wishes. Its task is to prepare and organize the Saturday meeting. Self-government does not deal with issues of teaching, nor does it perform intermediary functions between students and teachers.

lyami. The purpose of self-government in Summerhill is to organize the life of the school.

All participants in the meeting had the title of "citizens" and had the right to one vote (every child and every adult). After observing meetings for many years, Neill came to the conclusion that the success of the meeting depends on how much the chairman can manage the situation and create a working atmosphere. The chairman had the right to impose fines on the most noisy citizens, so if he was a weak organizer, then there were many fines. The head of the self-government also decided whether it was worth discussing the submitted issue or not.

The main function of self-government in Summerhill was the adoption or modification of laws that dealt with the basic rules of the hostel. In addition, which is no less important, all conflicts, wishes, complaints and problems of children were considered, that is, the self-government took care of approving the idea of protection. At the beginning of each semester, a general vote approved the end of the day (different for children of different ages), as well as the rules of general behavior. It also elected sports, dance and theater committees, an evening service that monitors the silence of the night, and a city service that monitors the behavior of children outside of school.

Further, cases concerning complaints and proposals were considered. Saturday general meetings usually revealed various conflicts between adults and children. In the list of such cases there are complaints about older children who were not allowed to sleep after lights out; to a boy who appropriated a board prepared for a lesson by a labor teacher and made a shelf; on one of the children who carried away the clay for classes without asking. All these complaints may seem to reflect the peculiar struggle between adults and children that allegedly existed in Summerhill. However, according to Neill, this is just a clash of an adult point of view and a child's vision of the same things. These conflicts show that Summerhill is alive, and in no way do they show aggression from either the children or the

adults. Hatred of elders arises only where children do not meet with respect for themselves.

Children dealt with offenders with remarkable impartiality and wisdom, and had an amazing sense of justice. All this procedure had an undoubted educational value. Very often, criticizing children as judges, they say that they can be very harsh. Summerhill's experiment states the opposite. Throughout its history, children have not accepted a single too harsh punishment. Moreover, the penalty was even associated with the nature of the offense. The children, of course, were unaware of the existence of the "method of natural consequences," but they acted in accordance with it. An example is the case of four boys who climbed a ladder owned by construction workers. The assembly decided that, as a punishment, they should go up and down the stairs for ten minutes without a break. In another case, two boys who threw clods of earth were ordered to bring earth in wheelbarrows and level the playground.

Some misdemeanors were followed by automatic punishments in the form of a fine, deprivation of pocket money, a ban on going to the cinema. Such violations include, for example, riding someone's bike without the owner's permission, misbehaving at the cinema, walking on the roof, throwing food in the dining room.

Usually the verdict of the assembly was taken as guilty. If not, he had the right to refuse the decision of the meeting. In this case, shortly before the end of the council, the chairman once again brought this issue up for discussion. Interestingly, the offenders never experienced anger or hatred at the punishment. First of all, because the punishments did not humiliate children morally. The only result was that the children were aware of their guilt and that they should be punished. It is also important to note that the meeting was organized and led by children from beginning to end. Only in very rare cases did children turn to adults with a request for advice.

The little owners of Summerhill were well aware of the importance of self-government in their lives. Were from-54

sensible moments in the history of the school, when there was a certain crisis in the development of self-government. So it was, for example, when no one wanted to be a candidate in the elections. Neill declared himself a dictator, and the children quickly realized that without the already familiar laws and rules that they themselves accept, it is impossible to arrange a normal life.

It has already been mentioned that Neill organized weekly meetings for the staff, at which various problems of psychology were discussed. The children felt they needed them too, especially those who were twelve years old. The pupils asked Neill to give them lectures on the psychology of adolescence, the psychology of theft, the psychology of the crowd, the psychology of humor. Thanks to these conversations, Summerhill pupils learned to understand their behavior, realized Neill's pedagogical views, which led to faster adaptation at school, awareness of its exclusivity compared to other education systems. Children also learned to understand each other, to be tolerant and attentive.

Summerhill society was very harsh on those who offended the weak and defenseless. Among the laws that were adopted by the self-government and which had to be strictly followed, was the following: "Severe punishment will follow for all cases of mockery of the weaker ones." But there were very few such cases in Summerhill's life. Neill believed that the main cause of childhood cruelty is the feeling of hatred that is born in response to the authoritarianism of adults. Not being able to pour out this enmity on the elders, children turn it on the younger and weaker ones. The atmosphere of life in Summerhill removed this cruelty in interpersonal relationships. If a child behaved unbearably, the entire children's society expressed their dissatisfaction. And since every child is interested in acceptance by society, he quickly learns to behave according to general rules. No drill or harsh discipline is simply needed.

Apart from difficult cases, Neill consistently enforced the rule that, regardless of 55

age each had the right to one vote. At the same time, Neill was aware that children under the age of twelve were not yet able to make independent decisions. Being in the majority, kids can even frustrate the reasonable proposals of the elders. However, according to Neill, if there is already a group of elders who are guided by the idea of goodness, it is possible and necessary to allow the little ones to participate in discussions on an equal footing. This is precisely the only way to teach children from an early age the democratic laws of the hostel, the formation of the ability to think independently and make independent decisions regarding their own problems and the problems of other people. Neill noted that a school in which there is no self-government cannot be called progressive at all. It is impossible to talk about the freedom of the child if children are not given complete freedom to manage their lives.

Self-government in Summerhill was constantly faced with the eternal problem of confrontation between the individual and the team. In such cases, the assembly often made decisions in favor of the collective. It should be noted once again that this concerned primarily children, whose actions restricted the freedom of others. Often, before the adoption of a harsh verdict, a certain time passed when the violator was tried to be convinced. However, according to Neill, society cannot and should not mess with one person. He believed in the power of public opinion. Once in Summerhill there was a pupil who mocked the younger ones, was hostile towards others. The children's community was forced to do something to protect the weak - and that meant speaking out against it. It was impossible to allow the mistakes of this boy's parents to be reflected in other children who were accustomed to care and love. Neill wrote that it was sometimes with great regret that he had to send a child away from Summerhill, because he kept everyone else in suspense.

Over the many years of Summerhill's existence, Neill has not changed his attitude towards self-government. "It is impossible to overestimate the educational value of such a practical science of rights and obligations 56

citizen. In Summerhill, children would fight to the end for the right to self-determination. In my opinion, one weekly general meeting is much more important than all the school subjects for the whole week put together. This is a great form of public speaking exercise and most kids do it without embarrassment. I have often heard quite reasonable reasoning of children who could neither read nor write.

Neill did not see any alternative to Summerhill democracy, believing that it was even fairer than political democracy in society, since children are mutually benevolent, and all laws are adopted at a general meeting, and there is never a problem of uncontrolled elected deputies. Thus, the children's self-government in Summerhill satisfied the children's need to independently organize their lives, established an atmosphere of security in the children's community and contributed to the solution of all emerging problems of interpersonal relationships.

Fundamentally refusing any teachings, suggestions of a religious and moral nature, Neill at the same time considered it necessary to help the child in his self-realization, a kind of individual therapy. He considered its main goal to promote the emotional release of a child who, due to various circumstances (alienation of parents or constant suppression by the school system), developed fear and aggressiveness on a neurotic basis. He borrowed this technique of individual therapy from Freud's psychoanalysis. Evidence of Neill's passion for Freudianism is also his very approaches to explaining the causes of certain deviations in the behavior of children.

Neill did not have any clear structure and method for conducting therapy. Usually it was an informal conversation by the fireplace, which began with questions directly related to the interlocutor. Only after overcoming distrust or any difficulties of free communication did he move on to problems related to his personality, family, and peers.

Sometimes the conversation began with the question: "When you look in the mirror, do you like your face?" The answer was usually negative. "What part of your face do you dislike?" Invariably, the children named the nose. Neill considered the face to be the outward image of the inner self. If a child says that he cannot stand his face, it means that he does not love himself. The next step is to move away from the face to the inner being of the child. "What do you hate most about yourself?" Often the answer concerns appearance: "My feet are too big. I'm very short. I have bad hair."

During the conversation, Neill never expressed his attitude to such answers, did not rush things, only listened carefully and reacted to the child's answers with an additional question and a request to continue. Neill then proceeded to talk about personality. To do this, he often used the following test: write down in the questionnaire how many percent this or that quality is developed in you. Here is an example of a fourteen-year-old boy's test.

"Good appearance: Oh, not so good, around 45%.

Sanity: Hmm, 60%.

Courage: 25%.

Loyalty: I never let my friends down. 80%.

Musicality: Zero.

Crafting Skill: Muttered something indistinct in response.

Hate: It's too hard. No, I can't answer it.

Sports games: 66%.

Public sentiment: 90%.

Stupidity: Oh, about 190%."

The main condition of therapy was the gaining of trust, the assertion in the child of confidence that the elder is on his side. In particularly difficult cases, Neill resorted to techniques that shocked the pupils, for example, he treated a student whom he saw smoking with a cigarette, or involved in an impromptu theft if he was dealing with a small thief. The shock caused by Neill's act usually became a turning point in the relationship.

relationship between an adult and a child and the beginning of a change in the behavior of the latter. With young children, Neill's therapeutic technique was even more spontaneous: he simply "walked" after the child.

Over time, Neill increasingly refuses therapy, convinced that the very freedom that reigns in school creates an opportunity for children to naturally get rid of complexes.

A characteristic feature of many experimental schools of the first half of the twentieth century was the appeal to artistic creation as a means to develop the sense of beauty in children most fully, to teach them to comprehend beauty in nature and in art, and thereby ennoble the soul. Art, according to Ovid, contributes to the softening of morals and prevents their coarsening. Developing the creative powers of the child, it contributes to his self-realization. Neill was also an ardent supporter of the use of the magical effects of art for educational purposes.

During all the years of its existence, a children's theater has been operating in Summerhill. Usually in winter every Sunday was a theater day. Sometimes for several weeks in a row there were various performances on the school stage.

Traditionally, only performances composed by the children themselves were staged on the Summerhill stage. Plays written by teachers were staged only if at the moment there was no ready-made children's text. Plays for children, according to Neill, should be based on their worldview. Children cannot be forced to play classical plays, the content of which is so far from children's life, from their perception and fantasy. (Nevertheless, it should be noted that during the long winter evenings Neill read Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov, Galsworthy to his pupils.)

Costumes and scenery were also prepared by the children themselves. The stage was mobile and consisted of boxes, the location of which changed depending on the intention of the authors.

Summerhilltsy showed excellent acting skills. There was absolutely no timidity or stiffness. The kids were especially sincere. 59

Girls usually performed more willingly than boys, and the latter, until the age of ten, preferred to play only in gangster performances. Interestingly, Neill notes, the worst actors were those who acted in real life; on the stage, they were embarrassed and did not find a place for themselves.

Neill considered the children's theater an important means of moral education. Each little actor should be able to put himself in the place of another person, and this teaches him to understand others, their feelings and experiences, which is very important in establishing good interpersonal relationships. The theater also solved the problem of strengthening self-confidence, and those children who refused to play found themselves in some other activity. Fourteen-year-olds refused to perform in love scenes, while the little ones took part in them with pleasure and without any embarrassment.

The elders were interested in stage technology and had their own original approach in this regard. If, for example, in ordinary dramaturgy an actor, leaving the stage, says aloud where and why he has gone, the children found this unnatural. They said that in real life no one does that, and therefore they tried to bring their game closer to life.

Very popular among the inhabitants of Summerhill were original mini-performances, exercises in theatrical technique, which were called spontaneous play. For example, it was necessary to complete tasks such as "Pick up a bouquet of flowers and find thistles among the flowers", "You dine at a restaurant at the railway station and sit on pins and needles, because you are afraid that the train will leave without you", etc. Sometimes exercises were in the nature of a spontaneous reaction in one common proposed scene. For example, Neill played the role of an immigration officer, and all the children with "passports" in their hands had to be ready to answer any of his questions; or he became a businessman looking for a secretary, or a producer looking for an actor for a role.

Spontaneous acting was an essential creative part of the school theater at Summerhill. The theater itself played 60

the greatest role in the development of children's creativity in comparison with all other activities.

Among these activities are dance and music. Dance in Summerhill was dedicated to a special day - Wednesday. Children danced with pleasure and at a good level. Neill believed that dance is a great means of self-expression, and a person who never dared to go out into the circle and make his own steps in the dance will never be able to find himself either in teaching, or in politics, or in religion. Therefore, any program in Summerhill included dances that one of the girls put on well. Most often these were dances not of a classical nature, but to jazz music. For example, Neill wrote the libretto to Gershwin's music "An American in Paris" and the girls danced it. Almost every day the children came to Neill's apartment to listen to records by Dick Ellington, E. Presley, Ravel and Stravinsky.

The creative self-expression of children in Summerhill was greatly facilitated by art workshops, where children drew, sculpted from clay, carved, sewed, and made various handicrafts. The main thing was that nothing to anyone not imposed, everyone searched, tried and did what what he liked it.

In the end, freedom of choice gave everyone the opportunity to open up, to feel their strength, their capabilities, to assert themselves in a childish environment. And this is the basis for achieving happiness, which was the goal, Summer Hill.

"FREE SCHOOL COMMUNITY" IN WIKKERSDORF

The Free School Community" was founded in 1906 in Wickersdorf (Thuringia, the Duchy of Saxe Meiningen, near Saalfeld) by the famous German humanist teacher Gustav Wieneken (1875-1964). The school existed until 1933. Due to its location in the bosom of nature, this school was often ranked to "new schools", 61

which were the most important phenomenon in the humanistic pedagogy of the XX century. However, such a comparison is far from accurate. Wieneken's "free school community" differed from many "new schools" both in the pedagogical concept of its founder and in the internal organization of the school, where students were given the freedom to decide on their own school life, regulate intra-school relations, and participate in organizing their studies and recreation.

How the "free school community" differs from the "rural nurseries" of G. Litz, the generally recognized organizer of the "new schools" movement in Germany, G. Wieneken himself revealed in his book "School and Youth Culture" (1913). In it, he calls the starting points for building a new system of education not the religious and national ideal, but unique children's and youth culture. According to Wieneken, separate school reforms cannot lead to any significant results, and therefore it is necessary to educate a "new generation". This can be done only in the "free school community" he created in Vickersdorf.

Wienecken developed his ideas later in the Vickersdorf Chronicles and various journal articles. The nature of the pedagogical manifesto for Wieneken is his book "The Struggle for Youth".

Wienecken was initially influenced by Nietzsche's philosophy, but gradually came to the conclusion that the Nietzschean strongman needed a "social complement". Therefore, in the concept of Wieneken, a synthesis of individualism with collectivism can be traced.

Wieneken built the new ideal of school education on the idea self-worth of youth. Traditional pedagogy sees in youth only a transitional stage from childhood to adulthood and does not recognize its independent value for a person. Therefore, adults consider themselves entitled to impose their worldview, their understanding of life and their way of life on young people. This leads to the fact that each generation leaves behind only its own reproduction, and this leads development into a dead end of endless monotony. Wherein

youth also suffers - as a result of the forcible imposition of a way of life alien to it, and maturity - because of the need to constantly give oneself to children. It turns out a vicious circle: youth is sacrificed to adulthood, which, in turn, is sacrificed to youth. To break this vicious circle, it is necessary that the goal of the school should not be preparation for a future life, but a special culture, a lifestyle inherent in youth. The school should not only feel this spirit of youth, but also cultivate it, become a center of youth culture. From an institution that has always had the goal of preparing for life, it must itself become the center of life.

Wienecken's worldview was greatly influenced by his connection with the children's and youth movement, mainly the "migratory birds" movement, which arose in 1897 and represented a curious phenomenon in German cultural life. If initially its task was the independent wanderings of schoolchildren around Germany during the holidays, then gradually, from a manifestation of innocent romance, this movement grew into a protest of young people against the bourgeoisie, against the philistine family, against school tyranny and perverted city life. Not satisfied with the present and striving for self-determination, young people tried to find themselves in the bosom of nature, in communication with the common people.

Wieneken saw this movement as a healthy beginning, expressing not so much the age-old craving of youth for vagrancy and play as a rejection of the vices of adult culture. And so, when, on the eve of the First World War, the German youth threw out the new slogan of "youthful culture," Wienecken took this idea under his protection. In his opinion, it does not hide the desire of young people to create some kind of their own culture, replacing the existing one with it. The younger generation simply does not want to be an appendage of adults, but seeks to fill their lives with beautiful natural content, the search for new forms of youth life, greater freedom and greater beauty.

Youth is, according to Wieneken, such a stage in the development of a personality that needs a certain isolation in a kind of "kingdom of youth". Precisely at 63

During this period, young men and women must master their youth culture with the help of experienced teachers and mentors, in order to later bring it to the treasury of human culture, thereby renewing the latter and breathing new life into it.

"Free school community" in Vickersdorf and became a kind of center of youth culture. The school was founded by a group of students and teachers of the "rural educational home" in Ilzenburg, dissatisfied with the conservatism of its leader. This fact largely determined the nature of the "free school community" as a union of teachers and students united by a common ideal of education. In this highly democratic experimental institution, the theoretical propositions put forward by Wieneken on the need for the emancipation of young people, their self-determination, and knowledge of the intrinsic value of youth were tested in practice.