The front line between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan, plus the Zod pass. Search results for \"front line \" Front line passing herds of collective farm cattle

Rear railway station on the way to the front. Water tower. Two straight old poplars. A low brick station surrounded by thick acacias.

The military train stops. Two village children run up to the carriage with wallets in their hands.

Lieutenant Martynov asks:

Why currant?

The elder replies:

We do not take money from you, comrade commander.

The boy conscientiously fills the glass astride, so that the currant falls on the hot dust between the sleepers. He knocks the glass into the bowler set up, cocks his head, and, listening to the distant rumble, announces:

- "Henkel" is buzzing ... Wow! Wow! Suffocated. Don't be afraid, comrade lieutenant, there they are our fighters. Here the Germans have no passage through the sky.

Axis! There it thumps...

Lieutenant Martynov is interested in this message. He sits down on the floor by the door and, dangling his legs out, eating currants, asks:

Hm! And what, lad, are people doing in that war?

They shoot, - the boy explains, - they take a gun or a cannon, point it ... and bam! And you're done.

What's ready?

That's what! - the boy exclaims with annoyance. - If they pull the trigger, pull it, then death will come.

To whom death - me? - And Martynov imperturbably pokes his finger in his chest.

No! - the boy screams distressedly, surprised by the dullness of the commander. - Some kind of evil spirit has come, throwing bombs at huts, at sheds. That's where the grandmother was killed, two cows were torn to pieces. About what, - he mockingly shamed the lieutenant, - he put on a revolver, but he doesn’t know how to fight.

Lieutenant Martynov is confused. The commanders around him laugh.

The locomotive gives a whistle.

The boy, the one who delivered the currants, takes his angry little brother by the hand and, striding towards the moving carriages, explains to him at length and indulgently:

They know! They are joking! This is such a people going ... cheerful, desperate! One commander handed me a three-ruble note for a glass of currants on the go. Well, I'm behind the wagon, running, running. But he put the paper into the car anyway.

Here ... - the boy nods approvingly. - You what! And he is there in the war, let him buy kvass or sitra.

That's stupid! - accelerating his pace and keeping level with the car, the elder says condescendingly. - Do they drink it in the war? Don't lean on my side! Don't turn your head! This is our "I-16" - a fighter, and the German is buzzing heavily, with a break. The war is on its second month, and you don't know your planes.

Combatant zone. Passing herds of collective farm cattle, which go to calm pastures to the east, to the crossroads of the village, the car stops.

A boy of about fifteen jumps up on the step. He is asking for something. The cattle lows, a long whip clicks in clouds of dust.

The engine rumbles, the driver honks desperately, driving away the stupid beast that will not turn off until it hits its forehead on the radiator. What does the boy need? We don't understand. Of money? Of bread?

Then suddenly it turns out:

Uncle, give me two bullets.

What do you need ammo for?

And so ... for memory.

They don't give you ammo for memory.

I shoved him a lattice shell from a hand grenade and a spent shiny cartridge case.

The boy's lips twitch in disdain.

Here you go! What's the point of them?

Ah dear! So you need a memory that you can use? Maybe give you this green bottle or this black, egg-shaped grenade? Maybe you should unhook that small anti-tank gun from the tractor? Get in the car, don't lie and say everything straight.

And so the story begins, full of secret omissions, evasions, although in general everything has long been clear to us.

The dense forest closed sternly around, deep ravines lay across the road, swampy reed swamps spread along the banks of the river. Fathers, uncles and older brothers leave to join partisans. And he is still young, but dexterous, bold. He knows all the hollows, the last forty-kilometer paths in the area.

Fearing that they will not believe him, he pulls out a Komsomol ticket wrapped in oilcloth from his bosom. And not having the right to say anything more, licking his chapped, dusty lips, he waits greedily and impatiently.

I look into his eyes. I put a clip in his hot hand. This is a clip from my rifle. She is registered to me.

I take responsibility for the fact that every bullet fired from these five rounds will fly exactly in the right direction.

What is your name?

Listen, Yakov, why do you need cartridges if you don't have a rifle? What are you going to shoot from an empty jug?

The truck is moving. Yakov jumps off the footboard, he jumps up and cheerfully shouts something awkward, stupid. He laughs and mysteriously threatens me with his finger. Then, moving his fist in the muzzle of a cow spinning near, he disappears in clouds of dust.

Oh, No! This kid will not lay the clip in an empty pot.

Children! The war fell on tens of thousands of them in exactly the same way as on adults, if only because the fascist bombs dropped over peaceful cities have the same effect on everyone.

Acutely, often more acutely than adults, teenagers are little boys, girls are experiencing the events of the Great Patriotic War.

They eagerly, to the last point, listen to the messages of the Information Bureau, remember all the details of heroic deeds, write out the names of the heroes, their ranks, their surnames.

With boundless respect they see off the echelons leaving for the front, with boundless love they greet the wounded arriving from the front.

I saw our children deep in the rear, in the troubled front line, and even on the front line itself. And everywhere I saw in them a great thirst for work, work, and even achievement.

Before the battle on the bank of a river, I recently met a boy.

Looking for the missing cow, in order to shorten the path, he swam across the river and suddenly found himself in the location of the Germans.

Hiding in the bushes, he sat three steps away from the fascist commanders, who were talking about something for a long time, holding a map in front of them.

He came back to us and told us what he saw.

I asked him:

Wait a minute! But you heard what their bosses said, it's very important for us.

The boy was surprised:

So they, Comrade Commander, spoke German!

I know it's not Turkish. How many classes did you complete? Nine? So you were supposed to at least understand something from their conversation?

He folded his hands sadly and sadly.

Oh, comrade commander! If I had known about this meeting before...

Years will pass. You will become adults. And then, at a good hour of rest after a great and peaceful work, you will remember with joy that once, in terrible days for the Motherland, you did not hang under your feet, did not sit idly by, but in what way you could help your country in its difficult and a very important fight against human-hated fascism.

Front line essay

Rear railway station on the way to the front. Water tower. Two straight old poplars. A low brick station surrounded by thick acacias.

The military train stops. Two village children run up to the carriage with wallets in their hands.

Lieutenant Martynov asks:

Why currant?

The elder replies:

We do not take money from you, comrade commander.

The boy conscientiously fills the glass astride, so that the currant falls on the hot dust between the sleepers. He knocks the glass into the bowler set up, cocks his head, and, listening to the distant rumble, announces:

- "Henkel" is buzzing ... Wow! Wow! Suffocated. Don't be afraid, comrade lieutenant, there they are our fighters. Here the Germans have no passage through the sky.

Axis! There it thumps...

Lieutenant Martynov is interested in this message. He sits down on the floor by the door and, dangling his legs out, eating currants, asks:

Hm! And what, lad, are people doing in that war?

They shoot, - the boy explains, - they take a gun or a cannon, point it ... and bam! And you're done.

What's ready?

That's what! - the boy exclaims with annoyance. - If they pull the trigger, pull it, then death will come.

To whom death - me? - And Martynov imperturbably pokes his finger in his chest.

No! - the boy screams distressedly, surprised by the dullness of the commander. - Some kind of evil spirit has come, throwing bombs at huts, at sheds. That's where the grandmother was killed, two cows were torn to pieces. About what, - he mockingly shamed the lieutenant, - he put on a revolver, but he doesn’t know how to fight.

Lieutenant Martynov is confused. The commanders around him laugh.

The locomotive gives a whistle.

The boy, the one who delivered the currants, takes his angry little brother by the hand and, striding towards the moving carriages, explains to him at length and indulgently:

They know! They are joking! This is such a people going ... cheerful, desperate! One commander handed me a three-ruble note for a glass of currants on the go. Well, I'm behind the wagon, running, running. But he put the paper into the car anyway.

Here ... - the boy nods approvingly. - You what! And he is there in the war, let him buy kvass or sitra.

That's stupid! - accelerating his pace and keeping level with the car, the elder says condescendingly. - Do they drink it in the war? Don't lean on my side! Don't turn your head! This is our "I-16" - a fighter, and the German is buzzing heavily, with a break. The war is on its second month, and you don't know your planes.

Combatant zone. Passing herds of collective farm cattle, which go to calm pastures to the east, to the crossroads of the village, the car stops.

A boy of about fifteen jumps up on the step. He is asking for something. The cattle lows, a long whip clicks in clouds of dust.

The engine rumbles, the driver honks desperately, driving away the stupid beast that will not turn off until it hits its forehead on the radiator. What does the boy need? We don't understand. Of money? Of bread?

Then suddenly it turns out:

Uncle, give me two bullets.

What do you need ammo for?

And so ... for memory.

They don't give you ammo for memory.

I shoved him a lattice shell from a hand grenade and a spent shiny cartridge case.

The boy's lips twitch in disdain.

Here you go! What's the point of them?

Ah dear! So you need a memory that you can use? Maybe give you this green bottle or this black, egg-shaped grenade? Maybe you should unhook that small anti-tank gun from the tractor? Get in the car, don't lie and say everything straight.

And so the story begins, full of secret omissions, evasions, although in general everything has long been clear to us.

The dense forest closed sternly around, deep ravines lay across the road, swampy reed swamps spread along the banks of the river. Fathers, uncles and older brothers leave to join partisans. And he is still young, but dexterous, bold. He knows all the hollows, the last forty-kilometer paths in the area.

Fearing that they will not believe him, he pulls out a Komsomol ticket wrapped in oilcloth from his bosom. And not having the right to say anything more, licking his chapped, dusty lips, he waits greedily and impatiently.

I look into his eyes. I put a clip in his hot hand. This is a clip from my rifle. She is registered to me.

I take responsibility for the fact that every bullet fired from these five rounds will fly exactly in the right direction.

What is your name?

Listen, Yakov, why do you need cartridges if you don't have a rifle? What are you going to shoot from an empty jug?

The truck is moving. Yakov jumps off the footboard, he jumps up and cheerfully shouts something awkward, stupid. He laughs and mysteriously threatens me with his finger. Then, moving his fist in the muzzle of a cow spinning near, he disappears in clouds of dust.

Oh, No! This kid will not lay the clip in an empty pot.

Children! The war fell on tens of thousands of them in exactly the same way as on adults, if only because the fascist bombs dropped over peaceful cities have the same effect on everyone.

Acutely, often more acutely than adults, teenagers are little boys, girls are experiencing the events of the Great Patriotic War.

They eagerly, to the last point, listen to the messages of the Information Bureau, remember all the details of heroic deeds, write out the names of the heroes, their ranks, their surnames.

With boundless respect they see off the echelons leaving for the front, with boundless love they greet the wounded arriving from the front.

I saw our children deep in the rear, in the troubled front line, and even on the front line itself. And everywhere I saw in them a great thirst for work, work, and even achievement.

Before the battle on the bank of a river, I recently met a boy.

Looking for the missing cow, in order to shorten the path, he swam across the river and suddenly found himself in the location of the Germans.

Hiding in the bushes, he sat three steps away from the fascist commanders, who were talking about something for a long time, holding a map in front of them.

He came back to us and told us what he saw.

I asked him:

Wait a minute! But you heard what their bosses said, it's very important for us.

The boy was surprised:

So they, Comrade Commander, spoke German!

I know it's not Turkish. How many classes did you complete? Nine? So you were supposed to at least understand something from their conversation?

He folded his hands sadly and sadly.

Oh, comrade commander! If I had known about this meeting before...

Years will pass. You will become adults. And then, at a good hour of rest after a great and peaceful work, you will remember with joy that once, in terrible days for the Motherland, you did not hang under your feet, did not sit idly by, but in what way you could help your country in its difficult and a very important fight against human-hated fascism.

active army

Rear railway station on the way to the front. Water tower. Two straight old poplars. A low brick station surrounded by thick acacias.

The military train stops. Two village children run up to the carriage with wallets in their hands.

Lieutenant Martynov asks:

Why currant?

The elder replies:

We do not take money from you, comrade commander.

The boy conscientiously fills the glass astride, so that the currant falls on the hot dust between the sleepers. He knocks the glass into the bowler set up, cocks his head, and, listening to the distant rumble, announces:

- "Henkel" is buzzing ... Wow! Wow! Suffocated. Don't be afraid, comrade lieutenant, there they are our fighters. Here the Germans have no passage through the sky.

Axis! There it thumps...

Lieutenant Martynov is interested in this message. He sits down on the floor by the door and, dangling his legs out, eating currants, asks:

Hm! And what, lad, are people doing in that war?

They shoot, - the boy explains, - they take a gun or a cannon, point it ... and bam! And you're done.

What's ready?

That's what! - the boy exclaims with annoyance. - If they pull the trigger, pull it, then death will come.

To whom death - me? - And Martynov imperturbably pokes his finger in his chest.

No! - the boy screams distressedly, surprised by the dullness of the commander. - Some kind of evil spirit has come, throwing bombs at huts, at sheds. That's where the grandmother was killed, two cows were torn to pieces. About what, - he mockingly shamed the lieutenant, - he put on a revolver, but he doesn’t know how to fight.

Lieutenant Martynov is confused. The commanders around him laugh.

The locomotive gives a whistle.

The boy, the one who delivered the currants, takes his angry little brother by the hand and, striding towards the moving carriages, explains to him at length and indulgently:

They know! They are joking! This is such a people going ... cheerful, desperate! One commander handed me a three-ruble note for a glass of currants on the go. Well, I'm behind the wagon, running, running. But he put the paper into the car anyway.

Here ... - the boy nods approvingly. - You what! And he is there in the war, let him buy kvass or sitra.

That's stupid! - accelerating his pace and keeping level with the car, the elder says condescendingly. - Do they drink it in the war? Don't lean on my side! Don't turn your head! This is our "I-16" - a fighter, and the German is buzzing heavily, with a break. The war is on its second month, and you don't know your planes.

Combatant zone. Passing herds of collective farm cattle, which go to calm pastures to the east, to the crossroads of the village, the car stops.

A boy of about fifteen jumps up on the step. He is asking for something. The cattle lows, a long whip clicks in clouds of dust.

The engine rumbles, the driver honks desperately, driving away the stupid beast that will not turn off until it hits its forehead on the radiator. What does the boy need? We don't understand. Of money? Of bread?

Then suddenly it turns out:

Uncle, give me two bullets.

What do you need ammo for?

And so ... for memory.

They don't give you ammo for memory.

I shoved him a lattice shell from a hand grenade and a spent shiny cartridge case.

The boy's lips twitch in disdain.

Here you go! What's the point of them?

Ah dear! So you need a memory that you can use? Maybe give you this green bottle or this black, egg-shaped grenade? Maybe you should unhook that small anti-tank gun from the tractor? Get in the car, don't lie and say everything straight.

And so the story begins, full of secret omissions, evasions, although in general everything has long been clear to us.

The dense forest closed sternly around, deep ravines lay across the road, swampy reed swamps spread along the banks of the river. Fathers, uncles and older brothers leave to join partisans. And he is still young, but dexterous, bold. He knows all the hollows, the last forty-kilometer paths in the area.

Fearing that they will not believe him, he pulls out a Komsomol ticket wrapped in oilcloth from his bosom. And not having the right to say anything more, licking his chapped, dusty lips, he waits greedily and impatiently.

I look into his eyes. I put a clip in his hot hand. This is a clip from my rifle. She is registered to me.

I take responsibility for the fact that every bullet fired from these five rounds will fly exactly in the right direction.

What is your name?

Listen, Yakov, why do you need cartridges if you don't have a rifle? What are you going to shoot from an empty jug?

The truck is moving. Yakov jumps off the footboard, he jumps up and cheerfully shouts something awkward, stupid. He laughs and mysteriously threatens me with his finger. Then, moving his fist in the muzzle of a cow spinning near, he disappears in clouds of dust.

Oh, No! This kid will not lay the clip in an empty pot.

Children! The war fell on tens of thousands of them in exactly the same way as on adults, if only because the fascist bombs dropped over peaceful cities have the same effect on everyone.

Acutely, often more acutely than adults, adolescents - boys, girls - experience the events of the Great Patriotic War.

They eagerly, to the last point, listen to the messages of the Information Bureau, remember all the details of heroic deeds, write out the names of the heroes, their ranks, their surnames.

With boundless respect they see off the echelons leaving for the front, with boundless love they greet the wounded arriving from the front.

I saw our children deep in the rear, in the troubled front line, and even on the front line itself. And everywhere I saw in them a great thirst for work, work, and even achievement.

Before the battle on the bank of a river, I recently met a boy.

Looking for the missing cow, in order to shorten the path, he swam across the river and suddenly found himself in the location of the Germans.

Hiding in the bushes, he sat three steps away from the fascist commanders, who were talking about something for a long time, holding a map in front of them.

He came back to us and told us what he saw.

I asked him:

Wait a minute! But you heard what their bosses said, it's very important for us.

The boy was surprised:

So they, Comrade Commander, spoke German!

I know it's not Turkish. How many classes did you complete? Nine? So you were supposed to at least understand something from their conversation?

He folded his hands sadly and sadly.

Oh, comrade commander! If I had known about this meeting before...

Years will pass. You will become adults. And then, at a good hour of rest after a great and peaceful work, you will remember with joy that once, in terrible days for the Motherland, you did not hang under your feet, did not sit idly by, but in what way you could help your country in its difficult and a very important fight against human-hated fascism.

active army

At the passage through a heavy barricade sheathed with rough wood, a policeman checked my pass to leave the besieged city. Read...

I was then thirty-two years old. Marusya is twenty-nine, and our daughter Svetlana is six and a half. Only at the end of the summer did I get a vacation, and for the last warm month we rented a dacha near Moscow.

1. Na-pi-shi-te so-chi-non-nie-ras-judging-de-nie, ras-roo-vaya meaning of you-saying-va-nia from the West-no-go ling-vi -sta Ru-be-na Alek-san-dro-vi-cha Bu-da-go-wa: “Sin-tak-sis always on-ho-dit-sya in the service of sa-mo-go -lo-ve-ka, his thoughts and feelings. Ar-gu-men-ti-ruya your answer, with-ve-di-te 2 (two) examples from the pro-chi-tan-no-go text-hundred. When-in-dya in-measures, indicate-zy-wai-te but-me-ra of the necessary pre-lo-same-ni or apply me-nyai-te qi-ti-ro-va-nie . You can pi-sat ra-bo-tu in an academic or public-li-qi-sty-che style, spreading the topic in ling-wi-sti-che ma-te-ri-a-le. Start co-chi-non-ing you can-those words-wa-mi R. A. Bu-da-go-va. The volume of co-chi-non-niya should be at least 70 words. Ra-bo-ta, na-pi-san-naya without relying on a pro-chi-tan-ny text (not according to a given text), do not appreciate it. If co-chi-non-nye represents a re-said or full-of-stu re-re-pi-san-ny source text without any there was no com-men-ta-ri-ev, then such a ra-bo-ta estimate-no-va-et-sya with zero points. Write an essay carefully, legible handwriting.

2. Na-pi-shi-te co-chi-not-nie-ras-judging-de-nie. Explain-no-those, how do you-no-ma-e-those the meaning of the pre-lo-zh-ny text-hundred: “I saw our children in the deep rear, in an alarming at the front-then-howl in a lo-se and even on the line of the sa-my front-ta. And everywhere I saw in them a great thirst for business, work, and even movement. At-ve-di-te in co-chi-non-nii 2 (two) ar-gu-men-ta from pro-chi-tan-no-go text-hundred, confirming your ras-judgment-de-niya. When-in-dya in-measures, indicate-zy-wai-te but-me-ra of the necessary pre-lo-same-ni or apply me-nyai-te qi-ti-ro-va-nie . The volume of co-chi-non-niya should be at least 70 words. If co-chi-non-nye represents a re-said or full-of-stu re-re-pi-san-ny source text without any there was no com-men-ta-ri-ev, then such a ra-bo-ta estimate-no-va-et-sya with zero points. Write an essay carefully, legible handwriting.

3. How do you know the meaning of the word-in-co-che-ta-tion FORCE OF THE SPIRIT? Sfor-mu-li-rui-te and pro-com-men-ti-rui-te given by you define de-le-ni. Na-pi-shi-te co-chi-non-nie-ras-judging-de-nie on the topic “What is the power of the spirit”, taking the definition given by you as a te-zi-sa -le-nie. Ar-gu-men-ti-ruya your thesis, with-ve-di-te 2 (two) with-me-ra-ar-gu-men-ta, confirming your races -de-nia: one example-mer-ar-gu-ment with-ve-di-te from pro-chi-tan-no-go text-hundred, and the second - from your life -no experience. The volume of co-chi-non-niya should be at least 70 words. If co-chi-non-nye represents a re-said or full-of-stu re-re-pi-san-ny source text without any there was no com-men-ta-ri-ev, then such a ra-bo-ta estimate-no-va-et-sya with zero points. Write an essay carefully, legible handwriting.

Active army, Komsomolskaya Pravda,

(1) Children! (2) The war fell on tens of thousands of them in the same way as on adults, if only because the fascist bombs dropped over peaceful cities have the same force for everyone. (3) Acutely, often more acutely than adults, adolescent boys, girls are experiencing the events of the Great Patriotic War. (4) They eagerly, to the last point, listen to the messages of the Information Bureau, remember all the details of heroic deeds, write out the names of the heroes, their ranks, their surnames. (5) With boundless respect they escort the echelons leaving for the front, with boundless love they meet the wounded arriving from the front.

(6) I saw our children in the deep rear, in the alarming front line, and even on the front line itself. (7) And everywhere I saw in them a great thirst for work, work, and even achievement.

(8) Front line. (9) Passing herds of collective farm cattle, which go to calm pastures to the east, to the crossroads of the village, the car stops. (10) A fifteen-year-old boy jumps on the step. (11) He asks for something. (12) What does the boy need? (13) We do not understand. (14) Bread? (15) Then suddenly it turns out:

- (16) Uncle, give me two rounds.

- (17) What do you need ammo for?

- (18) And so ... for memory.

- (19) They don’t give cartridges for memory.

(20) I thrust him a lattice shell from a hand grenade and a spent shiny shell. (21) The boy's lips curl contemptuously.

- (22) Well! (23) What's the use of them?

- (24) Oh, dear! (25) So you need such a memory with which you can make sense? (26) Maybe give you this black, egg, grenade? (27) Maybe you should unhook that small anti-tank gun from the tractor? (28) Get in the car, don't lie and say everything straight. (29) And now the story begins, full of secret omissions, evasions, although in general everything has long been clear to us.

(30) A dense forest closed around severely, deep ravines lay across the road, swampy reed swamps spread along the banks of the river. (31) Fathers, uncles and older brothers are leaving for partisans. (32) And he is still young, but dexterous, bold. (33) He knows all the hollows, the last paths for forty kilometers in the area. (34) Fearing that they would not believe him, he pulls out a Komsomol ticket wrapped in oilcloth from his bosom. (35) And not being entitled to tell anything more, licking his cracked, dusty lips, he waits eagerly and impatiently.

(36) I look into his eyes. (37) I put a clip in his hot hand. (38) This is a clip from my rifle. (39) It is written on me. (40) I take responsibility for the fact that each bullet fired from these five rounds will fly exactly in the right direction.

- (41) What is your name?

- (43) Listen, Yakov, why do you need cartridges if you don’t have a rifle? (44) What are you going to shoot from an empty clay bottle *?

(45) The truck moves off. (46) Jacob jumps off the footboard, he jumps up and cheerfully shouts something awkward, stupid. (47) He laughs, mysteriously threatens me with his finger and disappears in clouds of dust.

(48) Oh no! (49) This guy will not lay the clip in an empty bottle.

(50) Another case. (51) Before the fight, on the banks of one river, I met a guy. (52) Looking for the missing cow in order to shorten the path, he swam across the river and unexpectedly found himself in the location of the Germans. (53) Hiding in the bushes, he sat in three steps from the fascist commanders, who talked for a long time about something, holding a map in front of them. (54) He returned to us and told about what he saw. (55) I asked him:

Wait a minute! (56) But you heard what their bosses said, and you understood that this is very important for us.

(57) The boy was surprised:

So they, Comrade Commander, spoke German!

- (58) I know that it's not Turkish. (59) How many classes did you finish? (60) Nine? (61) So you should have at least understood something from their conversation?

(62) He sadly and sadly spread his hands:

- (63) Oh, comrade commander! (64) If only I knew about this meeting earlier ...

* Krynka - a jug, a pot for milk.

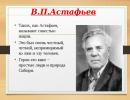

(According to A.P. Gaidar*)

* Gaidar Arkady Petrovich ( real name- Golikov, 1904-1941) - children's writer, screenwriter, participant in the Civil and Great Patriotic Wars.

In what way-ri-an-te from-ve-ta contains in-for-ma-tion, not-about-ho-di-may to justify-no-va-nia from-ve- she answered the question: “Why, par-nish-ka, having listened to the time of the non-mets-kih-man-di-ditch, I couldn’t re-give it with -holding the so-vet-skim sol-yes-there?

1) Non-metz-kie-man-di-ry go-vo-ri-li very quietly.

2) Par-nish-ka did not understand the content of this once-in-ra, because he did not learn the German language well at school.

3) Steam-nish-ka was not-attention-ma-te-len, then-ro-drank-sya, he was looking for his co-ro-woo.

4) Par-nish-ka didn’t hear a lot, because it’s a ri-co-val map of military actions.

Clear-no-no.

The sad sigh of the boy “If only I had known about this meeting earlier ...” he says that at school he didn’t teach German how to but, about which this hour was very sorry.

Answer: 2

Answer: 2

Source: FIPI Open Bank, block 634F69, RESHU option No. 108

Relevance: Used in the OGE 2016-2017

Clear-no-no.

1. 1. Let's take an example of co-chi-non-niya-ras-judging-de-niya in an academic style.

Sin-tak-sis - section of ling-vi-sti-ki, studying pre-lo-same and word-co-che-ta-nie. Pre-lo-zhe-nie - one-ni-tsa sin-so-si-sa, in a co-hundred-ve-swarm of separate words and pre-di-ka-tiv-ny parts with -ob-re-ta-yut ability to inter-and-mo-action-stvo-vat and about-ra-zo-you-vat re-che-com-po-nen-you. Therefore, it’s impossible not to agree with you-say-zy-va-ni-em from the West-no-go ling-wi-sta Ru-be-na Alek-san-dro -vi-cha Bu-da-go-va: “Sin-tak-sis is always on-ho-dit-sya in the service of sa-mo-go-lo-ve-ka, his thoughts and feelings."

To confirm the correctness of the words of R.A. Bu-da-go-va ob-ra-tim-sya to the tear-ku from the text-hundred Ar-ka-diya Gai-da-ra. Ras-look-rim pre-lo-zhe-niya 63-64. According to the content, these two proposals should be combined into one complex-subordinate. Why does the author divide them into two? What is the purpose? No-conditions-but, it's not-accidental. Such an or-ga-ni-za-tion pre-lo-zhe-ni-m-ha-et under-emphasize from-cha-i-ne boy-chi-ka, not so-mev-she-go understand what the fa-shist co-man-di-ry are talking about.

In se-re-di-not proposition 18 (And so ... for pa-min.) there is a lot of something: something par-niche-ka not-to-go -va-ri-va-et - it immediately becomes clear.

In this way, pro-ana-li-zi-ro-vav the text, we can confidently assert that syn-tak-sis plays not-a-little -an important role in you-ra-same-tion of our thoughts and pe-re-zhi-va-ny.

2. The war didn’t spare anyone: million-li-o-ns died, hundreds of thousands of children were left without ro-di-te-lei in the en-time. These older left-handed children strove to be worthy of their fathers and older brothers. About this, the final lines of the tek-sta Gai-da-ra: “I saw our children in the deep rear, in the anxious front-line, howling in the lo-se and even on the line of the sa-mo-go front-ta. And everywhere I saw in them a great thirst for business, work, and even movement.

Yakov is ready to fight with the enemy, he is young, re-shi-te-len and bold. That's why the fighter believes him and gives both pa-tro-nov. In preposition number 49 (This pa-re-nek for-lo-lives both-mu not in an empty kryn-ku) we-ho-dim confirm this.

In the preposition-lo-ni-yah 63-64 (“Oh, then-va-rishch commander-man-dir! If only I knew about this meeting earlier ...”) with no hiding -e-my do-sa-doy par-nish-ka-vo-rit that he did not learn a non-Mets language and did not understand what the fa-shist was talking about -skie co-man-di-ry, but he could bring valuable information.

War - is-py-ta-nie, war - raz-ru-she-nie, war - raz-lu-ka. But she won’t be able to do anything, because she’s pro-ti-in-on-be-le-on-ve-li-kaya fortitude on-she-on-ro -yes, where even a child is ready to compare his life with the life of his father-hero.

3. The strength of the spirit is one of the main qualities, de-la-yu-chee-lo-ve-ka strong. This is not-for-me-no-my quality, which helps you live in difficult life si-tu-a-qi-yah. A person, strong in spirit, is able to pre-ado-le-va, as-for-moose, not-pre-odo-whether-my obstacles. We-tea-neck on-the-strain of spiritual and physical forces in-tre-bo-wa-elk from our-she-on-ro-yes, so that you-stand in the Great Patriotic War. The children were also strong in spirit, who became adults so early.

Ar-ka-diy Gaydar de-lit-sya with chi-ta-te-la-mi not-you-du-man-ny-mi is-to-ri-i-mi about how to-everything boys-chish-ki, not being afraid of anything, help adults to beat the enemy. One asks for one hundred pas, and not for pas, but for through-you-tea-but important, tai-no-th business. The other regrets that he could not understand anything from the under-listen-shan-but-th-th-th-in-ra-fri-tsev, he could not help his own ... The desire of children to be on an equal footing with adults, to contribute to the be-do-not-evaluate-no-mo. And this is only possible for children whose spirit is strong and strong. Like fathers who went to the front.

About the fate of the mo-lo-do-wife, left alone with hunger, raz-ru-hoy, fear and death, I learned from the film ma "Ma-ter che-lo-ve-che-sky". How-for-elk, how can you live in such conditions? But Mary could. And not only she herself remained alive: she saved the lives of children who lost their parents. Together they sowed bread, ho-ho-wa-whether for zhi-here-us-mi and lived in hope for the return of Russian soldiers-dates, for help. And they waited! But the film would not have an op-ti-mi-stich-no-th end if it were not for the strength of the spirit of Mary. This film is a hymn to a strong Russian woman.

Happiness is to meet people on your way, stubborn, left-wing, stubborn. But every person should strive to for-mine the strength of the spirit, because you-keep-reaping vital tests only such people can do it.

13. Determine the sentence in which both underlined words are spelled ONE. Open the brackets and write out these

two words.

A. N. Ostrovsky paid serious attention to the work on the language all his life: he followed (FOR) WHAT (WOULD) each

the phrase corresponded to the idea put forward.

A hare jumped out of the thicket to the edge, but, having made a jump, (THAT) HOUR rushed (TO) LEAK.

HARDLY (DURING) TIME we will be able to hide from the rain.

(NOT) LOOKING at the parted linen curtains, the candles still burned with a steady, unblinking light.

The actor went out to the platform, arranged (B) IN THE FORM of a spacious glass pavilion (C) BEHIND the car.

14. Specify the number (- s), in the place of which (-s) is written HH.

To obtain high quality paper, crushed (1), impregnated (2) with a special (3) composition, boiled (4) with a special

temperature, tree trunks should be converted (5) into a fluid mass.

15. Set up punctuation marks. Write two sentences in which you need to put ONE comma. write down

numbers of these proposals.

1) Purpose in life is the core of human dignity and human happiness.

2) Some kind of force pulled Margarita up and placed her in front of a mirror, and a royal diamond flashed in her hair.

3) For the poem “The Death of a Poet”, full of sorrow and civil indignation, M. Yu. Lermontov was arrested and

exiled to the Caucasus.

4) The artists drew with a pencil and pen in oils and watercolors.

5) There are many troubles, sorrows and sorrows in life, and sometimes it is not easy to overcome them.

16. -s), in the place of which (-s) must(- s) stand comma( th).

A majestic animal (1) frozen in a few tens of meters from us (2) shook its branched horns

(3) and (4) having taken off from the place (5) disappeared into the thicket.

17. Put all the punctuation marks: indicate the number(-s), in the place of which (-s) must(- s) stand comma( th).

To many now (1) perhaps (2) it will seem strange that even some hundred years ago in Russia there was not a single

there were no art lovers in Russia at all.

18. Put all the punctuation marks: indicate the number(-s), in the place of which (-s) must(- s) stand comma( th).

The path of the expedition (1) (2) which (3) included several local guides (4) began not far from

coast.

19. Place all punctuation marks: indicate all the numbers in the place of which commas should be in the sentence.

It was quiet in the house (1) and (2) if it were not for the bright fire in the window (3), one would think (4) that everyone was already sleeping there.

20. Edit the sentence: correct the lexical error by replacing misused word. write down

chosen word, observing the norms of the modern Russian literary language.

A series of lectures were devoted to the work of A.P. Chekhov, at which excerpts from his work were read.

Read the text and complete tasks 21 - 26

(1) Frontline. (2) Passing herds of collective farm cattle, which go to calm pastures to the east, to

At the crossroads of the village, the car stops. (3) A fifteen-year-old boy jumps up on the step.

-(4) Uncle, give me two cartridges.

-(5) What do you need ammo for?

- (6) And so ... for memory.

- (7) They don’t give cartridges for memory.

(8) I thrust him a lattice shell from a hand grenade and a spent shiny cartridge case.