The main ideas of the concept of Russian socialism. The ideology of socialism in Russia. Stability of the social structure

The main provisions of the theory of “Russian socialism” were developed by Alexander Ivanovich Herzen(1812-1870). The main thing for Herzen was the search for forms and methods of combining the abstract ideas of socialism with real social relations, ways of implementing the theoretical (“book”) principles of socialism. Herzen deeply experienced the suppression by the bourgeoisie of the uprising of the Parisian proletariat in June 1848 as a defeat of socialism in general: “The West is rotting,” “the philistinism is triumphant.” Soon (by 1849-1850) Herzen came to the conclusion that the country in which it is possible to combine socialist ideas with historical reality is Russia, where communal land ownership has been preserved.

The Russian peasant world, he argued, contains three principles that make it possible to carry out an economic revolution leading to socialism: 1) everyone’s right to land, 2) communal ownership of it, 3) secular management. These communal principles, embodying “elements of our everyday, immediate socialism,” wrote Herzen, hinder the development of the rural proletariat and make it possible to bypass the stage of capitalist development: “The man of the future in Russia is a man, just like in France a worker.”

In the 50s Herzen founded the Free Russian Printing House in London, where the newspaper “The Bell” was printed (since 1857), which was illegally imported into Russia.

According to Herzen, the abolition of serfdom while preserving the community would make it possible to avoid the sad experience of capitalist development in the West and move directly to socialism. “We,” wrote Herzen, “ Russian socialism we call that socialism that comes from the land and peasant life, from the actual allotment and the existing redistribution of fields, from communal ownership and communal management - and goes together with the workers' artel towards that economic justice, which socialism in general strives for and which science confirms."

Herzen considered the community that existed in Russia to be the basis, but by no means a ready-made cell of the future social order. He saw its main drawback in the absorption of the individual into the community.

The peoples of Europe, according to Herzen’s theory, developed two great principles, bringing each of them to extreme, flawed solutions: “The Anglo-Saxon peoples liberated the individual, denying the social principle, isolating man. The Russian people preserved the communal structure, denying personality, absorbing man.”

The main task, according to Herzen, is to combine individual rights with the communal structure: “To preserve the community and liberate the individual, to spread rural and volost self - government * on cities, on the state as a whole, while maintaining national unity, developing private rights and preserving the indivisibility of the land - this is the main question of the Russian revolution - the same as the question of great social liberation, the imperfect solutions of which so worry Western minds."

* Self management.

Herzen paid great attention to ways to implement the social revolution. In his works there are many judgments about the inevitability of the violent overthrow of capitalism: “No matter how much socialism pursues its question, it has no other solution than a crowbar and a gun.” However, Herzen was by no means a supporter of mandatory violence and coercion: “We do not believe that peoples cannot move forward except knee-deep in blood; we bow with reverence to the martyrs, but with all our hearts we wish that they did not exist.”

During the preparation period peasant reform in Russia, the Bell expressed hopes for the abolition of serfdom by the government on terms favorable to the peasants. But the same “Bell” said that if the freedom of the peasants is bought at the price of Pugachevism, then this is not too expensive a price to pay. The most rapid, unbridled development is preferable to maintaining the order of Nikolaev stagnation.

Herzen's hopes for a peaceful solution to the peasant question aroused objections from Chernyshevsky and other revolutionary socialists. Herzen answered them that Rus' should be called not “to the axe,” but to the brooms, in order to sweep away the dirt and rubbish that had accumulated in Russia.

“Having called for an ax,” Herzen explained, “you must master the movement, you must have organization, you must have a plan, strength and readiness to lay down your bones, not only grabbing the handle, but grabbing the blade when the ax diverges too much.” There is no such party in Russia; therefore, he will not call for an ax until “there remains at least one reasonable hope for a solution without an ax.”

In those same years, Herzen developed the idea of electing and convening a nationwide, classless “Great Council” - a Constituent Assembly to abolish serfdom, legitimize the propaganda of socialist ideas, and the legitimate struggle against autocracy. "Whatever first Constituent Assembly, first parliament, - he emphasized, “we will receive freedom of speech, discussion and legal ground under our feet.” Starting with Herzen, the idea of a Constituent Assembly became an organic part of the social-revolutionary and democratic ideology of Russia.

Disappointment with the results of the reform of 1861 strengthened Herzen's revolutionary sentiments. However, it was clear to him that if with the help of revolutionary violence it is possible to abolish autocracy and the remnants of serfdom, then it is impossible to build socialism in this way: “With violence you can destroy and clear a place - no more. With Petrograndism* the social revolution goes beyond the convict equality of Gracchus Babeuf and the communist corvée of Cabet will do." In the article “To an Old Comrade” (1869-1870), Herzen argues with Bakunin, who continued to mistake destructive passion for creative passion.”** “Does civilization with a whip, liberation with a guillotine constitute the eternal necessity of every step forward?”

* Petrograndism is the transformation of society by state power using violent methods, like Peter I (the Great).

** Herzen alludes to an article by Bakunin (under the pseudonym Jules Elizard) in the German Yearbook for 1842, which ends with the phrase: “The passion for destruction is at the same time a creative passion!”

The state, church, capitalism and property are condemned in the scientific community in the same way as theology, metaphysics and so on, Herzen wrote; however, outside of academia, they command many minds. "(It is just as impossible to bypass the question of understanding as it is to bypass the question of strength."

From the ruins of the bourgeois world, destroyed by violence, some other bourgeois world arises again. An attempt to quickly, on the fly, without looking back, move from the current state to the final results will lead to defeats; A revolutionary strategy must look for the shortest, most convenient and possible paths to the future. “By walking forward without looking back, you can squeeze in like Napoleon into Moscow - and die retreating from it.”

Herzen paid special attention to the “international union of workers” (i.e. MTR, International) as “the first network and the first shoot of the future economic structure.” The International and other unions of workers "must become a free parliament of the fourth state." “Their serious nature,” Herzen wrote about the MTR congresses, “struck the enemies. Strong their peace frightened the manufacturers and breeders."

In the theory of “Russian socialism” by Herzen, the problems of state, law, and politics were considered as subordinate to the main ones - social and economic problems. Herzen attributed the era of purely political revolutions to the past stages of history; transformations of state forms and constitutional charters have exhausted themselves. Herzen has many opinions that the state does not have its own content at all - it can serve both reaction and revolution, depending on which side has the power. The Committee of Public Safety destroyed the monarchy, the revolutionary Danton was the Minister of Justice, the autocratic tsar initiated the liberation of the peasants. “Lassalle wanted to use this state power,” Herzen wrote, “to introduce a social order. Why, he thought, break the mill when its millstones can grind our flour too?”

The view of the state as something secondary in relation to the economy and culture of society in Herzen’s reasoning is directed against the ideas of Bakunin, who considered the primary task of destroying the state. “An economic revolution,” Herzen objected to Bakunin, “has an immense advantage over all religious and political revolutions.” The state, like slavery, wrote Herzen (referring to Hegel), is moving towards freedom, towards self-destruction; however, the state “cannot be thrown off like dirty rags until a certain age.” "From the fact that the state is a form transient, - Herzen emphasized, “it does not follow that this form is already past."

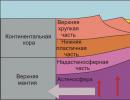

Herzen envisioned the future society as a union of associations (from the bottom up) of self-governing communities: “The rural community represents for us a cell that contains in embryo a state structure based on self-legality, on a world gathering, with an electoral administration and an elected court. This cell will not remain isolated, it forms a fiber or fabric with the adjacent communities, their connection - the volost - also manages its affairs and at the same elective basis."

A prominent theorist and propagandist of the ideas of “Russian socialism” was also Nikolai Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky(1828-1889). One of the leaders of the Sovremennik magazine in 1856-1862, Chernyshevsky, devoted a number of articles to the systematic presentation and popularization of the idea of the transition to socialism through the peasant community, with the help of which, in his opinion, Russia could avoid the “ulcer of the proletariat.”

In the article “Criticism of Philosophical Prejudices against Communal Ownership,” Chernyshevsky sought to prove, on the basis of Hegel’s law of the negation of the negation, the need to preserve the community and its development into a higher organization (according to the triad: primitive communalism - private property system - collectivist or communist society). For developed countries, “which have lost all consciousness of the former communal life and are only now beginning to return to the idea of the partnership of workers in production,” Chernyshevsky, in the article “Capital and Labor,” outlined a plan for organizing production partnerships with the help of a loan from the government, assigning one year to a new partnership experienced director. The organization of production and agricultural partnerships was very similar to Fourier's phalanxes, and the plan for their creation was set out close to the ideas of Louis Blanc.

Herzen called Chernyshevsky one of the outstanding representatives of the theory of not Russian, but “purely Western socialism.” Chernyshevsky indeed often referred to the ideas of Fourier, Leroux, Proudhon, Louis Blanc and other Western European socialists. However, the core of Chernyshevsky’s theory was the idea of communal socialism in Russia developed by Herzen. In turn, Herzen’s thoughts about the transition of the West (where the community did not survive) to socialism through the “workers’ artel” essentially coincided with the ideas of Western European socialists and Chernyshevsky. Disputes between Herzen and Chernyshevsky on individual problems did not go beyond disagreements within one direction, and the general goal was clearly formulated by Herzen: “The great task, the solution of which falls on Russia, is the development of folk elements through the organic development of the science of society developed by the West.” .

Chernyshevsky, along with Herzen, is deservedly considered the founder of the theory of “Russian socialism.”

Herzen, for all the originality and depth of his thinking and great literary talent, was not inclined to a methodical, popular and systematic presentation of his socio-political ideas. His works are not always complete; they often contain not conclusions, but reflections, sketches of plans, polemical hints, individual thoughts, sometimes contradictory. According to the recollections of contemporaries, during their meeting in London (1859), Chernyshevsky even complained that Herzen had not put forward a certain political program - constitutional, or republican, or socialist. In addition, “The Bell” and other publications of the Free Russian Printing House were distributed illegally in Russia; Not everyone could familiarize themselves with the articles expounding the theory of “Russian socialism” in full. This theory became the property of all reading Russia through Sovremennik.

In Chernyshevsky’s articles, the ideas of the development of communal land ownership into social production, and then consumption, received a thorough, popular and thoroughly reasoned presentation in a manner and form that corresponded to the socio-political consciousness of the heterogeneous intelligentsia. Wide erudition, amazing efficiency and talent as a publicist, along with the acute socio-political orientation of his magazine, brought Chernyshevsky the glory of the ruler of the thoughts of the radically thinking youth of his time. A significant role in this was played by the revolutionary tone of Sovremennik, which occupied an extremely left-wing critical position in journalism during the period of preparation and implementation of the peasant reform.

Chernyshevsky considered it most desirable to change the civil institutions of the nation through reforms, since “historical events” such as those in the 17th century. occurred in England, and later in France, are too expensive for the state. However, for contemporary Russia, Chernyshevsky considered the path of reform impossible. Using the terminology of N.A. Dobrolyubov, he defined autocracy with its bureaucratic apparatus and predilection for the nobility as “tyranny,” “Asianism,” “bad governance,” which once gave rise to serfdom, and is now trying to change its form while preserving its essence.

In journalistic articles, in essays on the history of France, in reviews of various works, Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov conducted anti-government revolutionary propaganda, using Aesopian language, parabolas, allusions and historical parallels. “If we had written in French or German,” Chernyshevsky explained to readers, “we would probably have written better.” The revolution was designated in the magazine as “a broad, original activity”, “important historical events that go beyond the ordinary order by which reforms are carried out”, etc.

The structure of power that would replace the overthrown autocracy was briefly discussed in the proclamation “Bow to the lordly peasants from their well-wishers” (1861), attributed to Chernyshevsky. This proclamation approved countries in which the people's elder (in foreign language - president) is elected for a term, as well as kingdoms where the king (like the British and French) does not dare to do anything without the people and shows obedience to all the people.

In Sovremennik, Chernyshevsky argued that political forms are important “only in relation to the economic side of the matter, as a means of helping economic reforms or delaying them.” At the same time, he noted that “no important news can establish itself in society without a preliminary theory and without the assistance of public power: it is necessary to explain the needs of the time, recognize the legitimacy of the new and give it legal protection.” It was obviously assumed that there would be a government responsible to the people that would ensure the transition to socialism and communism.

The need for a state, according to Chernyshevsky, is generated by conflicts caused by the discrepancy between the level of production and the needs of people. As a result of the growth of production and the transition to distribution according to needs (the principle of Louis Blanc), conflicts between people will disappear, and thereby the need for the state. After a long transition period (at least 25-30 years), the future society will develop into a federation of self-government unions of agricultural communities, industrial agricultural associations, factories and plants that have become the property of workers. In the article “Economic Activity and Legislation,” Chernyshevsky, decrying the theory of bourgeois liberalism, argued that state non-interference in economic activity is ensured only by replacing the private property system with communal ownership, which is “completely alien and contrary to the bureaucratic system.”

The Sovremennik criticized Western European liberal theories and developing constitutionalism. “All constitutional amenities,” wrote Chernyshevsky, “have very little value for a person who has neither the physical means nor the mental development for these desserts of a political kind.” Referring to the economic dependence of workers, Chernyshevsky argued that the rights and freedoms proclaimed in Western countries are generally a deception: “Right, understood by economists in an abstract sense, was nothing more than a ghost, capable only of keeping the people in the torment of an ever-deceived hope.”

The negative attitude of the theorists of “Russian socialism” towards formal equality and parliamentarism subsequently contributed greatly to the fundamentally negative attitude of the populists (until 1879) towards the political struggle, towards constitutional rights and freedoms.

After the abolition of serfdom, there was a decline in the spread and development of the ideas of “Russian socialism”. About the decade 1863-1873. Lavrov (see below) wrote that it was “a dull, tedious and lifeless time.”

In 1873, the “going to the people” of hundreds and thousands of propagandists began, and the following year, took on a massive scale, calling on the peasants to overthrow the tsar, officials and police officers, to a communal structure and governance. In emigration, the publication of Russian literature of a social revolutionary direction has increased. By 1876, the populist organization “Land and Freedom” had formed. The ideological basis of populism was the theory of “Russian socialism”. In the process of implementing this theory, different directions were identified within populism, each with its own ideologists.

Anarchist theorist M. A. Bakunin was also a recognized ideologist of populism (see § 3). He believed that Russia and the Slavic countries in general could become the center of a nationwide, all-tribal, international social revolution. The Slavs, in contrast to the Germans, did not have a passion for state order and state discipline. In Russia, the state openly opposes the people: “Our people deeply and passionately hate the state, hate all its representatives, no matter in what form they appear before them.”

Bakunin noted that the Russian people have “the necessary conditions for a social revolution. They can boast of excessive poverty, as well as exemplary slavery. Their sufferings are endless, and they do not endure them patiently, but with deep and passionate despair, which has already been expressed twice historically.” , two terrible explosions: the rebellion of Stenka Razin and the Pugachev revolt, and which has not ceased to manifest itself to this day in a continuous series of private peasant revolts."

Based on the basic principles of the theory of “Russian socialism,” Bakunin believed that the basis of the Russian folk ideal were three main features: first, the land belongs to the people; secondly, the right to use it not by an individual, but by an entire community, the world; thirdly (no less important than the two previous features), “community self-government and, as a result, a decidedly hostile attitude of the community towards the state.”

At the same time, Bakunin warned, the Russian folk ideal also has obscuring features that slow down its implementation: 1) patriarchy, 2) absorption of the person by the world, 3) faith in the Tsar. The Christian faith can be added as a fourth feature, Bakunin wrote, but in Russia this issue is not as important as in Western Europe. Therefore, social revolutionaries should not put the religious question at the forefront of propaganda, since religiosity among the people can only be killed by social revolution. Its preparation and organization is the main task of the friends of the people, educated youth, calling the people to a desperate rebellion. “We need to suddenly raise all the villages.” This task, Bakunin noted, is not easy.

A general popular uprising in Russia is hampered by the isolation of communities, the solitude and disunity of peasant local worlds, wrote Bakunin. It is necessary, observing the most pedantic caution, to connect with each other the best peasants of all villages, volosts, and, if possible, regions, to establish the same living connection between factory workers and peasants. Bakunin came up with the idea of a national newspaper to promote revolutionary ideas and organize revolutionaries.

Calling on educated youth to promote, prepare and organize a nationwide revolt, Bakunin emphasized the need to act according to a clearly thought-out plan, on the basis of the strictest discipline and secrecy. At the same time, the organization of social revolutionaries must be hidden not only from the government, but also from the people, since the free organization of communities should emerge as a result of the natural development of social life, and not under any external pressure. Bakunin sharply condemned doctrinaires who sought to impose on the people political and social schemes, formulas and theories developed outside the life of the people. Related to this are his rude attacks against Lavrov, who put the task of scientific propaganda at the forefront and envisioned the creation of a revolutionary government to organize socialism.

Bakunin's followers were called "rebels" in the populist movement. They began to circulate among the people, trying to clarify the consciousness of the people and induce them to spontaneous rebellion. The failure of these attempts led to the fact that the Bakuninist rebels were supplanted (but not supplanted) by “propagandists” or “Lavrists”, whose task was not to push the people to revolution, but to systematically revolutionary propaganda, enlightenment, and train conscious fighters for the social revolution in the countryside.

Petr Lavrovich Lavrov (1823-1900) from 1873 in exile he published the magazine “Forward!” He wrote a number of works that propagated the theory of “Russian socialism.” Lavrov highly valued science and sought to substantiate the theory of socialism with the latest achievements of political economy, sociology and natural sciences. “Only the successes of biology and psychology,” Lavrov asserted, “prepared in our century the correct formulation of the questions of scientific socialism.” He assessed Marx’s theory as “the great theory of the fatal economic process,” especially for its criticism of Western European capitalism, which corresponds to the aspirations of Russian socialists to bypass this stage of development in Russia.

A well-known contribution to the theory of “Russian socialism” was the “formula of progress” derived by Lavrov:"Development of the individual in physical, mental and moral terms; embodiment of truth and justice in social forms."

Socialism in Russia, Lavrov wrote, was prepared by its economic system (communal land use) and will be achieved as a result of a widespread popular revolution, which will create a “people's federation of Russian revolutionary communities and artels.”

Unlike Bakunin, Lavrov considered the state an evil that cannot be destroyed immediately, but can only be brought “to a minimum incomparably less than the minimums that previous history represented.” The state will be reduced to a "bare minimum" as moral education society, affirmation of solidarity (the less solidarity in a society, the more powerful the state element).

Lavrov defined the main provisions (“battle cry”) of workers’ socialism as follows: "End the exploitation of man by man.

Ending the control of man by man.

In the last formula, of course, the word “management” should be understood not in the sense of the voluntary subordination of one person in this case to the leadership of another, Lavrov explained, but in the sense coercive power one person over another."

Polemicizing with Tkachev’s “Jacobin theory” (see below), Lavrov wrote that “every dictatorship spoils the best people... A dictatorship can only be wrested from the hands of dictators by a new revolution.” And yet, to build socialism, according to Lavrov, state power is necessary as a form of leadership of collective activity and the use of violence against the internal enemies of the new system.

The significant differences between Lavrov and Bakunin boiled down to the fact that while the former considered the state only a means to achieve social goals, the latter noticed the tendency of the state to become an end in itself; Bakunin’s objections, as noted, were also caused by Lavrov’s intention to build a new society according to the developed scientific plan, prefacing the people’s revolution with an indefinitely long period of propaganda.

He was also a theorist of populism Petr Nikitich Tkachev(1844-1885). Since 1875, he published (in Geneva) the magazine "Alarm" with the epigraph: "Now, or very soon, perhaps - never!"

Unlike other populists, Tkachev argued that forms of bourgeois life were already emerging in Russia, destroying the “principle of community.” Today the state is a fiction that has no roots in people’s life, Tkachev wrote, but tomorrow it will become constitutional and will receive the powerful support of the united bourgeoisie. Therefore, we must not waste time on propaganda and preparing the revolution, as the “propagandists” (Lavrov’s supporters) suggest. “Such moments are not frequent in history,” Tkachev wrote about the state of Russia. “To miss them means to voluntarily delay the possibility of social revolution for a long time, perhaps forever.” “The revolutionary does not prepare, but “makes” the revolution.” At the same time, Tkachev considered it useless to call the people to revolt, especially in the name of communism, which is alien to the ideals of the Russian peasantry. Contrary to the opinion of the “rebels” (Bakunin’s supporters), anarchy is the ideal of the distant future; it is impossible without first establishing the absolute equality of people and educating them in the spirit of universal brotherhood. Now anarchy is an absurd and harmful utopia.

The task of revolutionaries, according to Tkachev, is to speed up the process of social development; “It can accelerate only when the advanced minority has the opportunity to subordinate the rest of the majority to its influence, that is, when it seizes state power into its own hands.”

A party of mentally and morally developed people, i.e. minority must gain material strength through a violent coup, Tkachev argued. “The immediate goal of the revolution should be the seizure of political power, the creation of a revolutionary state. But the seizure of power, being a necessary condition for the revolution, is not yet a revolution. It is only its prelude. The revolution is carried out by a revolutionary state.”

Tkachev explained the need for a revolutionary state led by a minority party by the fact that communism is not the popular ideal of the peasantry in Russia. The historically established system of the peasant community creates only the preconditions for communism, but the path to communism is unknown and alien to the people's ideal. This path is known only to the minority party, which, with the help of the state, must correct the backward ideas of the peasantry about the people's ideal and lead it along the road to communism. "The people are not able to build such a new world“, which would be able to progress, develop in the direction of the communist ideal,” Tkachev wrote, “therefore, in building this new world, he cannot and should not play any outstanding, leading role. This role and this significance belong exclusively to the revolutionary minority."

Tkachev disputed the widespread opinion among populists about the corrupting influence of power on statesmen: Robespierre, Danton, Cromwell, Washington, having had power, did not become any worse for it; as for the Napoleons and Caesars, they were corrupted long before they came to power. According to Tkachev, a sufficient guarantee of serving the good of the people will be the communist beliefs of members of the ruling party.

With the help of the revolutionary state, the ruling party will suppress the overthrown classes, re-educate the conservative majority in the communist spirit and carry out reforms in the field of economic, political, and legal relations (“revolution from above”). Among these reforms, Tkachev named the gradual transformation of communities into communes, the socialization of the instruments of production, the elimination of intermediation in exchange, the elimination of inequality, the destruction of the family (based on inequality), the development of community self-government, the weakening and abolition of the central functions of state power.

The social revolutionary party "Land and Freedom", organized in 1876, fundamentally rejected the struggle for political rights and freedoms, for the constitution. Populist Stepnyak-Kravchinsky wrote (in 1878) that socialist revolutionaries could hasten the fall of the government, but would not be able to take advantage of constitutional freedom, since political freedom would strengthen the bourgeoisie (owners of capital) and give it the opportunity to unite into a strong party against the socialists. Hope remains only for a socio-economic revolution. In addition, among the socialist revolutionaries of the time of the Land and Freedom party, there was a widespread negative attitude towards formal law as a bourgeois deception. Chernyshevsky's reasoning became widely known. “Neither me nor you, reader,” he wrote, addressing the readers of Sovremennik, “is forbidden to dine on gold service; unfortunately, neither you nor I have and probably never will have the means to satisfy this elegant idea; therefore, I frankly say that I do not value at all my right to have a gold service and am ready to sell this right for one ruble in silver or even cheaper. All those rights that liberals are fussing about are exactly the same for the people."

The government’s organized and tireless persecution of socialists, exiles, expulsions, trials in cases of “revolutionary propaganda in the empire” forced the populists to raise the question of the need to first conquer political freedoms, which would make it possible to conduct socialist propaganda. In 1879, “Land and Freedom” split into two parties: “Narodnaya Volya” (recognized the need for political struggle) and “Black Redistribution” (remained in its previous positions). In this regard, one of the leaders of “Narodnaya Volya” Kibalchich wrote about three categories of socialists: some adhere to Jacobin tendencies, strive to seize state power and decree a political and economic revolution (“Alarm” by Tkachev); others (“Black Redistribution”) deny the significance of political forms and reduce everything to the economic sphere; the third ("Narodnaya Volya") provide a synthesis of both, based on the connection and interaction of economics and politics, stand for a political revolution based on the overdue economic revolution, for the unity of action of the people and the social revolutionary party.

The theory of “Russian socialism” and populism were widely known throughout Europe. A number of populists were members of the Geneva section of the First International (mostly “Laurists”) and supported Marx’s struggle against Bakunin and the Bakuninists. The hostile relationship between Herzen and Marx, and then the rivalry between Marx and Bakunin for dominance in the First International, left an imprint on a number of Marx’s judgments about populism as the desire to “leap at one fell swoop into an anarchist-communist-atheist paradise.” However, a thorough solution by the theory of “Russian socialism” to the question posed by Fourier about the possibility of transition from lower stages of social development to higher ones, bypassing capitalism, required a well-founded analysis and assessment of this theory. In a number of published works, Marx and Engels (in the preface to the 1882 Russian edition of the Communist Manifesto, in Engels’ response to Tkachev’s polemical article in 1875, etc.) wrote that Russian communal land ownership could become the starting point of communist development under conditional on the victory in Western Europe of the proletarian revolution, which will provide the Russian peasantry with the material means and other conditions necessary for such development.

Populist ideas underlay the program of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (Socialist Revolutionaries, 1901-1923). The party set the task of overthrowing the tsarist government and considered armed uprising and terrorist actions to be one of the main means of combating it, i.e. murders and attempts on the lives of responsible representatives of this government.

The programmatic demands of the Socialist Revolutionary Party were the establishment of a democratic republic, broad autonomy for certain regions of the country, a federal structure of the state, the right of nationalities to freedom of development and cultural autonomy. The program provided for universal suffrage, election of officials for a certain period of time and the right to “replace” them by the people, full civil equality, separation of church and state, universal equal and compulsory education at state expense, and replacement of the standing army with a people's militia. To implement this program, the party demanded the convening of a Constituent Assembly, which, on behalf of the people, should establish a new political system.

In the socio-economic field, socialist revolutionaries were supporters of the socialization of the land, i.e. transferring it to the disposal of democratically organized local communities and cultivating the land with personal labor on the basis of equal land use. On the labor issue, the party demanded a reduction in the working day (no more than 8 hours), the introduction of state insurance for workers, freedom of professional associations, legislative labor protection, etc.

Recognizing the irreconcilable opposition between the class interests of the bourgeoisie and the working masses, the party set as its ultimate goal the abolition of private ownership of the forces of nature and the means of production, the elimination of the division of society into classes and the establishment of planned labor of all for the common benefit.

The Socialist Revolutionary Party carried out propaganda work in the countryside and in the city, persistently emphasizing that the working population is a single working class, the key to the liberation of which is the awareness of this unity; The party fundamentally rejected the opposition between the proletariat and the peasantry.

The motto of the Socialist Revolutionary Party was the words: “In the struggle you will find your right!”*

* See: Anthology of world political thought. In five volumes. T. V. Political documents. M., 1997. pp. 191-195.

In 1917, socialist revolutionaries actively contributed to the creation and development of the Soviets. Splits in the Socialist Revolutionary Party, the closure of the Constituent Assembly by the Bolsheviks in January 1918, in which the Socialist Revolutionaries had a majority, and then their exclusion from the Soviets and mass repressions after the events of July 1918 led to the liquidation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

History of Russia in the 18th-19th centuries Milov Leonid Vasilievich

§ 3. The origin of “Russian socialism”

European socialist ideas and Russian society. Second quarter of the 19th century. was a time of rapid spread of socialist ideas in Europe, which gained strength in France, England and the German lands. Varieties of socialism found expression in the writings of thinkers, politicians and fashionable writers. The works of Saint-Simon, F. R. Lamennais, C. Fourier, V. Considerant, E. Cabet, B. Disraeli, R. Owen, George Sand, and later C. Marx and P. J. Proudhon were included in the reading circle of the enlightened public . The socialist idea was simple and attractive. It was based on the denial of the principle of private property, criticism of bourgeois relations and belief in the possibility of building a society where there would be no exploitation of man by man. Such a society was called communist. The objective basis of interest in socialism was the deep contradictions characteristic of early bourgeois society, where free competition had no social restrictions, which gave rise to the deepest antagonism between rich and poor. The crisis of traditional society and the widespread collapse of the “old order” with their class definition were perceived by many contemporaries as convincing evidence of the need for new social relations.

The ideas of socialism penetrated into Russia. Denouncing the imitative nature of noble society, which was cut off from the Russian people by Peter's reforms, Khomyakov ridiculed the changeability of public sentiment from Catherine's to Nicholas's time. He correctly wrote about how the French-style encyclopedists were replaced by German-mystical humanists, whom “thirty-year-old socialists” are now ready to supplant. The founder of Slavophilism concluded: “It’s only sad to see that this instability is always ready to take upon itself the production of mental food for the people. It’s sad and funny, and, fortunately, it’s also dead, and that’s why it’s not grafted into life.” Khomyakov's assertion that socialism in Russia is dead, that its ideas are alien to the common people, was reckless. Chaadaev, who had amazing social insight, was more right when he asserted: “Socialism will win not because it is right, but because its opponents are wrong.”

The origin of interest in socialist teachings dates back to the early 1830s. and was associated with the attention with which the advanced strata of Russian society followed the revolutionary changes of 1830–1831. in Western Europe, when socialism first entered the political arena. In 1831, a circle was formed among the students of Moscow University, where the main role was played by A. I. Herzen and N. P. Ogarev. The views of young people, among whom were N. I. Sazonov, V. V. Passek, N. X. Ketcher, N. M Satin, were not distinguished by certainty; they preached “freedom and struggle in all four directions.” Members of the circle professed admiration for the ideals of the Decembrists and the French Revolution, rejected official patriotism, sympathized with the rebel Poles, and read Western European political literature. Three years after the establishment of the circle, its members, accused of singing “libel songs”, which the authorities considered the freedom-loving songs of Bérenger, were arrested and exiled. The circle of Herzen and Ogarev was the first to clearly show interest in the ideas of socialism, which were understood as “ the whole world new relationships between people." The members of the circle discussed the works of Fourier and Saint-Simon and, according to Ogarev, swore: “we will devote our whole lives to the people and their liberation, we will make socialism the basis.”

Young students were far from independently developing socialist ideas. Equally far from this were numerous Russian admirers of the novels of George Sand, who sang social equality and equal rights for women. At the same time, changes gradually took place in society, which gave I.V. Kireevsky the basis to declare that political issues that occupied the people of the previous generation were moving into the background and that progressive thinkers “stepped into the realm of social issues.”

V. G. Belinsky. V. G. Belinsky played an outstanding role in this process. A literary critic whose magazine debut occurred in the mid-thirties, he was a true ruler of the thoughts of young people. More than one generation was brought up on his articles. I. S. Aksakov admitted: “I traveled a lot around Russia: the name of Belinsky is known to every young man of any kind, to anyone thirsting for fresh air among the stinking swamp of provincial life.” In the censored press, Belinsky knew how to defend the ideas of true democracy, social justice and personal freedom. He was the first Russian publicist to talk about the importance of social issues, the future solution of which he linked with upholding the rights of a free individual: “What does it matter to me that the common life lives when the individual suffers.”

Belinsky's ideological evolution was not easy; he was characterized by extremes, a transition from one stage of development to another. He associated social changes, the need for which was obvious to him, either with the education of the people, or with autocratic initiative, or with revolutionary upheavals. At different times, he wrote enthusiastically about the Jacobins and Nicholas I. Belinsky's strength lay in his sincerity and ability to persuade. He met the beginning of the “wonderful decade” by reconciling himself with the Nikolaev reality, which he justified by misunderstanding Hegel’s formula “everything that is real is rational.” Having overcome “forced reconciliation,” Belinsky came to the idea of “education in sociality.” His motto in the 1840s. became the words: “Sociality, sociality - or death!” From here Belinsky concluded: “But it’s ridiculous to think that this can happen by itself, with time, without violent coups, without blood.” His criticism of social relations of the past and present - “denial is my God” - is associated with faith in the golden age of the future. This faith naturally led to the idea of socialism, which, as he admitted, “became for me the idea of ideas, the being of being, the question of questions, the alpha and omega of faith and knowledge. Everything is from her, for her and to her.”

Belinsky's socialism is a dream of a great and free Russia, where there is neither serfdom nor autocratic tyranny. His socialist idea also included criticism of bourgeois society, which he conducted from democratic and patriotic positions: “It is not good for the state to be in the hands of capitalists, and now I will add: woe to the state, which is in the hands of capitalists, these are people without patriotism. For them, war or peace means only the rise and fall of funds - beyond that they see nothing.”

Belinsky was greatly influenced by the ideas of Christian socialism. He wrote: “There will be no rich, there will be no poor, no kings and subjects, but there will be brothers, there will be people, and, according to the verb of the Apostle Paul, Christ will surrender his power to the Father, and the Father-Reason will reign again, but in the new heaven and over the new land."

In 1847, shortly before his death, Belinsky wrote the famous Salzbrunn letter to Gogol, which became his political testament. Criticizing Gogol’s “fantastic book”, his “Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends,” which contained a justification of despotism and serfdom, Belinsky spoke about the honorable role of Russian writers, in whom society sees “its only leaders, defenders and saviors from the darkness of autocracy, Orthodoxy and nationality " He described Nikolaev Russia as a country where “people trade in people,” where “not only are there no guarantees for personality, honor and property, but there is not even police order, but there are only huge corporations of various official thieves and robbers.” Rejecting Gogol’s religious and political instructions, he wrote that Russia “needs not sermons (she has heard them enough!), not prayers (she has repeated them enough!), but the awakening in the people of a sense of human dignity, lost for so many centuries in dirt and dung, of rights and laws consistent not with the teachings of the church, but with common sense and justice, and their strict implementation, if possible.”

For reading this letter aloud, Dostoevsky was sentenced to death. Belinsky’s final conclusion gives reason to see in him, first of all, a strong defender of law and civil dignity, those values that united Russian liberalism and Russian democracy: “The most living, modern national issues in Russia now: the abolition of serfdom, the abolition of corporal punishment, the introduction, if possible, of strict enforcement of those laws that already exist.”

Belinsky was a merciless exposer of not only official ideology, but also Slavophilism. Westerners considered him one of “ours.” But Herzen’s confession is noteworthy: “Except for Belinsky, I disagreed with everyone.” In the philosophical debates that people waged in the forties, Belinsky was inferior to many, but his conviction in the need to strive for practical action made him, in the words of I. S. Turgenev, the “central nature” of his time. Under the influence of communication with Belinsky, Herzen wrote: “I was lost (following the example of the 19th century) in the sphere of thinking, and now I have again become active and alive to the nails, my very anger restored me in all practical prowess, and, what’s funny, in this very point we met Vissarion and became each other’s partisans. Never more vividly have I felt the need to translate, no, develop philosophy into life.” In the public life of Russia, Herzen and Belinsky really occupied a special position, acting as heralds of the ideas of socialism. They had few direct followers. These include N.P. Ogarev and M.A. Bakunin.

Petrashevites circle. The establishment of socialist ideas in Russia was facilitated by M. V. Butashevich-Petrashevsky, a graduate of the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum, who served as a translator at the St. Petersburg customs. His duties included inspecting foreign books imported into Russia, which gave him the opportunity to compile a rich library that included socialist literature. In the mid-1840s. Progressive youth began to gather in his apartment - officials, officers, students, writers. They read books, some of which were banned in Russia, discussed them and made attempts to apply what they read to Russian reality. Many famous people attended Petrashevsky’s “Fridays”: writers M. E. Saltykov-Shchedrin, F. M. Dostoevsky, A. N. Maikov, A. N. Pleshcheev, N. G. Chernyshevsky, artist P. A. Fedotov. In addition to Petrashevsky, a prominent role was played by people from his inner circle: S. F. Durov, N. A. Speshnev, D. D. Akhsharumov, N. S. Kashkin. The propaganda of socialist ideas among students at St. Petersburg University was carried out by N. Ya. Danilevsky, the future author of the book “Russia and Europe.”

The “Pocket Dictionary of Foreign Words”, which Petrashevsky conceived, served to disseminate advanced ideas. It explained the words key to understanding the systems of Fourier and Saint-Simon, and explained the ideals of the French Revolution. One of Petrashevsky’s followers recalled: “Petrashevsky greedily grabbed the opportunity to disseminate his ideas with the help of a book that seemed completely insignificant; he expanded its entire plan, adding proper names to ordinary nouns, introduced with his power into the Russian language such foreign words that no one had used before - all this in order to set out under different headings the foundations of socialist teachings and list the main articles of the constitution , proposed by the first French constituent assembly, to make a poisonous criticism of the current state of Russia and indicate the titles of some works of such writers as Saint-Simon, Fourier, Holbach, Cabet, Louis Blanc."

The direction of Petrashevsky's circle was socialist. The head of the circle, as the investigative commission later noted, “brought his visitors to the point that, if not all of them became socialists, they already received new views and convictions on many things and left his meetings more or less shocked in their beliefs and inclined towards a criminal direction.” "

For Petrashevsky, socialism was not “a whimsical invention of a few whimsical heads, but the result of the development of all mankind.” Among socialist systems, he gave preference to Fourier's teaching, where the main emphasis was on the social organization of labor, social harmony and the full satisfaction of the material and spiritual needs of the individual. Fourier believed in the power of example and in the peaceful transition to socialist relations. He promoted phalanstery - a cell of the future, and Petrashevites made attempts to introduce phalanstery in Russia. The Russian Fourierists were more radical than Fourier, and at a dinner dedicated to his memory, Petrashevsky said: “We have condemned real social life to death, we must carry out our sentence.” Akhsha-rumov spoke there, whimsically combining a beautiful utopia, destructive principles and conviction in the proximity of socialist changes, which will begin in Russia: “Destroy capitals, cities and use all their materials for other buildings, and this whole life of torment, disasters, transform poverty, shame, disgrace into a luxurious, harmonious life, fun, wealth, happiness, and cover the entire poor land with palaces, fruits and decorate it with flowers - this is our goal. Here, in our country, we will begin the transformation, and the whole earth will finish it. Soon the human race will be freed from unbearable suffering.”

Among the “Fridays” participants there were vague conversations about the need for reforms, which meant both “a change of government” and the improvement of the court, the abolition of class privileges. They talked about the structure of Russia on a federal basis, when individual peoples would live based on their “laws, customs and rights.”

The Petrashevites rejected official patriotism and condemned the country where life and air were “poisoned by slavery and despotism.” Nicholas I was especially hated - “not a man, but a monster.” Petrashevites criticized everything: the government and the bureaucratic apparatus, legislation and the judicial system. They believed that “Russia is rightly called the classic country of bribery.” They considered serfdom to be the main evil of Russian life, when “tens of millions suffer, are burdened by life, and are deprived of the rights of humanity.” They saw the abolition of serfdom as a measure that the government itself was obliged to take. Petrashevsky stood for reforms carried out from above, but in the circle there was talk of a “general explosion.” Petrashevites believed that everything “depends on the people.” The radically minded Speshnev argued that the future revolution would be a people's revolution. peasant uprising and serfdom will cause him. He even developed a plan to “cause a rebellion within Russia through a peasant uprising.” Few shared his point of view.

Under the impression of the European events of 1848, some members of the circle, whose “Fridays” were open in nature, conceived the idea of creating secret society. They saw their goal as “without sparing themselves, to take full open participation in the uprising and fight.” The matter did not go further than talk, and later the investigation admitted that “Petrashevsky’s meetings did not constitute an organized secret society.”

In the spring of 1849, the main participants in Petrashevsky’s meetings were arrested. The authorities were well informed about what happened on “Fridays” and decided to put a limit to dangerous conversations. The investigation into the Petrashevites case revealed a clash of interests between two departments: the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which insisted on uncovering a serious anti-government conspiracy, and III Division, whose officials spoke of a “conspiracy of ideas.” The verdict of the military court was harsh: 21 people, including Petrashevsky and Dostoevsky, were sentenced to death, which at the last minute was replaced by hard labor. The main points of the accusation were plans to overthrow the state structure and to “completely transform social life.” It is curious that Danilevsky, who did not hide his participation in the propaganda of Fourierism, was punished mildly because he avoided talking about political topics. The ideas of socialism themselves did not seem dangerous to the Nikolaev authorities.

Spiritual drama by A. I. Herzen. After 1848, the interest of Russian society in the ideas of socialism did not decrease. Herzen was a direct witness to the revolutionary events in France: the overthrow of King Louis-Philippe, the proclamation of the republic, the coming to power of successive representatives of the interests of the class, which he called “philistinism” and which in reality was the bourgeoisie. He welcomed the collapse of the old order in Europe, the guarantors of which were Nicholas I and Metternich. However, the further development of the revolution became a shock for Herzen, his spiritual drama. He saw how the new authorities limited the rights of the common people, how the Republican General Cavaignac shot a peaceful demonstration of Parisian workers putting forward social demands. Herzen became disillusioned with the political revolution and the “philistine civilization” of the West; he became entrenched in the idea of the opposite paths of development of Russia and Europe. Spiritual drama did not mean disappointment in the ideals of socialism.

For Herzen, the European revolutionary upheavals became a prologue, a rehearsal for the future. In 1850, he addressed the Slavophiles as if on behalf of the Westerners: “Any day can overturn the dilapidated social building of Europe and drag Russia into the turbulent stream of a huge revolution. Is it time to prolong a family quarrel and wait for events to get ahead of us, because we have not prepared either the advice or the words that perhaps are expected of us? Don't we have an open field for reconciliation? And socialism, which so decisively, so deeply divides Europe into two hostile camps - is it not recognized by the Slavophiles just as it is by us? This is a bridge where we can give each other a hand.”

While building the building of “Russian socialism,” Herzen, cut off from Russia, was mistaken about the Westerners and Slavophiles. Socialism was alien to Khomyakov and Granovsky, Samarin and Kavelin. The peasant community, “discovered” by the Slavophiles, was not for them a prerequisite for socialism, as for Herzen, but a condition that excluded the emergence of a proletariat in Russia. Herzen and the Slavophiles were united by their belief in the inviolability of communal foundations. Herzen was sure: “It is impossible to destroy the rural community in Russia unless the government decides to exile or execute several million people.”

Community socialism. He wrote about this in the article “Russia”, in a series of works created at the height of Nikolaev’s “dark seven years”. Having borrowed a lot from the Slavophiles, Herzen turned to the community that has existed in Russia “from time immemorial” and thanks to which the Russian people are closer to socialism than the European peoples: “I see no reason why Russia must necessarily undergo all phases of European development, without I also see why the civilization of the future must necessarily be subject to the same conditions of existence as the civilization of the past.” This statement is the essence of Herzen’s “Russian” or communal socialism. For Herzen, the peasant community was the guarantee of the moral health of the Russian people and the condition for their great future. The Russian people “have preserved only one fortress, which has remained impregnable for centuries - their land community, and because of this they are closer to the social revolution than to the political revolution. Russia comes to life as a people, the last in a series of others, still full of youth and activity, in an era when other peoples dream of peace; he appears proud of his strength, in an era when other nations feel tired and at sunset.”

Herzen wrote: “We call Russian socialism that socialism that comes from the land and peasant life, from the actual allotment and the existing redistribution of fields, from communal ownership and communal management - and comes together with the workers' artel towards the economic justice to which socialism in general strives and which science confirms.”

Following the Slavophiles, he understood the economic principles of the peasant land community as equality and mutual assistance, the absence of exploitation, as a guarantee that “a rural proletariat is impossible in Russia.” He especially emphasized that communal land ownership is opposed to the principle of private property and, therefore, can be the basis for building a socialist society. He wrote: “The rural community represents, so to speak, a social unit, a moral personality; the state should never have encroached on it; the community is the owner and subject to taxation; she is responsible for each and every individual, and therefore is autonomous in everything that concerns her internal affairs.” Herzen believed it was possible to extend the principles of community self-government to city residents and the state as a whole. He proceeded from the fact that communal rights would not limit the rights of private individuals. Herzen was building a social utopia; it was a type of European utopian consciousness. At the same time, this was an attempt to develop an original socialist doctrine based on the absolutization of the historical and socio-political characteristics of Russia. Over time, based on Herzen’s constructions, theories of Russian, or communal, socialism developed, which became the essence of populist views.

Herzen paid special attention to the destruction of obstacles that prevent us from moving “toward socialism.” By them he understood imperial power, which since the time of Peter I has brought political and social antagonism into Russian life, and landowner serfdom, a “shameful scourge” weighing down on the Russian people. He considered the primary task to be the liberation of the peasants, subject to the preservation and strengthening of communal land ownership. He suggested that the initiative in liberation should be taken either by the Russian nobility or by the government, but more often he spoke about the liberating nature of the future social revolution. Here his views were not consistent.

Free Russian printing house. In 1853 he founded the Free Russian Printing House in London. He said: “If I do nothing more, then this initiative of Russian glasnost will someday be appreciated.” The first publication of this printing house was an appeal to the Russian nobility “Yuriev Day! St. George's Day! ”, in which Herzen proclaimed the need to liberate the peasants. He was afraid of Pugachevism and, turning to the nobles, he invited them to think about the benefits of “liberating the peasants with land and with your participation.” He wrote: “Prevent great disasters while it is in your will. Save yourself from serfdom and the peasants from the blood that they will have to shed. Have pity on your children, have pity on the conscience of the poor Russian people.”

Outlining the foundations of the new teaching - communal socialism, Herzen explained: “The word socialism is unknown to our people, but its meaning is close to the soul of the Russian man, who is living out his life in the rural community and in the workers’ artel.” In the first work of the free Russian press, the foresight was expressed: “In socialism, Rus' will meet revolution.” In those years, Herzen himself was far from believing in the imminent onset of revolutionary events in Russia, and his addressee, the Russian nobility, thought even less about it. In another leaflet, “Brothers in Rus',” he called on the noble society and all progressive people to take part in the common cause of liberation. In Nikolaev's time, this vague call was not heard.

Herzen was the first to declare the possibility of victory in Russia for the socialist revolution, which he understood as a people's, peasant revolution. He was the first to point out that it was Russia that was destined to lead the path to socialism, along which, as he believed, the rest of the European nations would follow. At the heart of Herzen’s foresight: rejection of Western “philistinism” and idealization of the Russian community. His teaching, the foundations of which he outlined in the last years of Nicholas's reign, was a notable stage in the development of European socialist thought. It testified both to the commonality of the ideological quest that took place in Russia and Western Europe, and to the futility of the efforts of Nicholas’ ideologists, and to the collapse of Nicholas’ ideocracy.

From a historical perspective, the desire of Nicholas I and his ideologists to establish complete control over society was fruitless. It was during his reign that the liberal and revolutionary socialist directions of the liberation movement arose and took ideological shape, the development and interaction of which soon began to determine the fate of Russian thought, the state of public life and, ultimately, the fate of Russia.

From the book of Molotov. Semi-power overlord author Chuev Felix IvanovichWithout socialism? We have lunch - appetizer: jellied meat, herring, butter, onion; first: kharcho; second: meat and potatoes. Molotov crawled down into the basement with a flashlight and brought a bottle of Gurjaani. “They said, I would climb down,” I tell him. “Oh, come on,” he says. He is eighty-eighth

From the book The Third Project. Volume III. Special Forces of the Almighty author Kalashnikov Maxim Kovalev Sergey IvanovichThe Origin of Literature The appearance of literature in Rome was naturally associated with the advent of writing, and the latter with the alphabet, which very early, even in the pre-Republican era, was borrowed by the Romans from the Greeks of Southern Italy. Determine with any certainty

From the book Secrets of Underwater Espionage author Baykov E AThe origin of the idea The idea of the possibility of listening to Soviet submarine cable communication lines first appeared at the end of 1970 from the already mentioned James Bradley, head of the underwater operations department of the US Navy Intelligence Agency. Perhaps he has this idea

From the book Peter I. The Beginning of Transformations. 1682–1699 author Team of authorsThe Origin of the Fleet Peter's interest in marine science arose in 1687–1688, when he heard from Prince Ya. F. Dolgoruky about the existence of an instrument that measured long distances from one point. The astrolabe (this is what we were talking about) was soon brought to the Tsar from France. Looking for

author From the book History of Spain IX-XIII centuries [read] author Korsunsky Alexander Rafailovich From the book History of Spain IX-XIII centuries [read] author Korsunsky Alexander Rafailovich From the book Empire for Russians author Makhnach Vlaidmir LeonidovichTroubles. Destroyers of Russian society and the Russian city Order, opposing the chaos of the Time of Troubles, is a corporate organization of householders, or more precisely, households. In Greek it is “demos”, and in Russian it is “society”. A full-fledged citizen at all times among all peoples -

From the book History of Economics: lecture notes author Shcherbina Lidiya Vladimirovna2. The Birth of Capitalism The trading and usurious capital of Florence (the famous Medici firm) financed the city's wool industry. Florentine wholesale cloth merchants had large funds and were able to purchase raw wool in England and

From the book Everyone, talented or untalented, must learn... How children were raised in Ancient Greece author Petrov Vladislav ValentinovichThe Origin of Pedagogy As we have already noted, the word “pedagogy” is of Greek origin. And this, of course, is not accidental. It was the ancient Greeks who were the first to not only consciously set themselves the task of becoming harmoniously developed people, but also to think about

From the book Russian-Lithuanian nobility of the 15th–17th centuries. Source study. Genealogy. Heraldry author Bychkova Margarita EvgenievnaThe origins of the bureaucratic apparatus of the Russian state. Genealogical notes The problem of the origin and evolution of the Russian state apparatus and the closely related problem of the composition of the bureaucratic apparatus has long attracted the attention of researchers. By virtue of

From the book Mission of Russia. National doctrine author Valtsev Sergey VitalievichThe origin of man is the origin of spirituality. Spirituality is as ancient a phenomenon as man himself. Since the beginning of his evolution, man has had spirituality. Actually, this is obvious, because spirituality is a distinctive characteristic of a person. There is spirituality - there is

From the book History of Political and Legal Doctrines. Textbook / Ed. Doctor of Law, Professor O. E. Leist. author Team of authors§ 5. Political and legal ideology of “Russian socialism” (populism) The main provisions of the theory of “Russian socialism” were developed by Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (1812-1870). The main thing for Herzen was the search for forms and methods of combining abstract ideas of socialism with real ones

In the 30s, they talked a lot and enthusiastically about utopian socialism in Russia, but the transfer of European socialism to Russian soil was carried out by A.I. Herzen (1812-1870) and N.P. Ogarev (1813-1877), who with good reason can be considered the founders of “Russian socialism”.

Initially, the ideas of the founders of “Russian socialism” about the upcoming social reorganization were very vague and not devoid of religious overtones. But already in the early 40s, their socialist views were formalized conceptually and moved from letters and diaries into philosophical journalism, becoming a fact of public consciousness. Taking the baton from the Decembrists, Herzen and Ogarev directed liberation thought in a new direction. By combining it with the ideas of socialism, they created a unique historiosophical construct - “Russian socialism”, which was a response to certain requests for national spiritual development and the result of a search for other paths than those followed by the post-revolutionary West.

The formation of the concept of “Russian socialism” took place under the significant influence of disappointments in previous forms of socialist utopianism. Herzen and Ogarev acted as the most consistent and profound critics of capitalism. They rejected not only its socio-economic foundations, based on private ownership of the means of production, but also the entire way of life, which they called bourgeois philistinism, “unbridled acquisitions.” Criticism of capitalism naturally led to the idea of Russia “leapfrogging” the bourgeois stage, which later took shape in the theory of non-capitalist development. The idea was supported, firstly, by references to objective socio-economic prerequisites, which were associated with the community, which was absent in the Western “formula” of development. A community capable of development and ensuring the free development of the individual was thought of as the foundation, the embryo of a future society. The community was seen as a social structure that could connect the present and future of the country with the least “costs” and at a faster pace. It is important that the significance of the achievements of Western civilization in this movement was not at all denied. The task, Herzen and Ogarev believed, was to, while preserving all the “universal human education” that had really taken root in Russia, to develop the “national principle” associated with “public property rights and self-government.” Secondly, statements in favor of Russia’s “leapfrog” through the capitalist phase of development were supported by references to the idea of the advantage of “lagging behind” peoples.

The idea of a “leap” found its historiosophical justification in Herzen’s philosophy of chance: the future belongs to Russia, but the very possibility of getting ahead is connected with the fact that the course of history is not as predetermined as is usually thought, for there are many changeable principles and, accordingly, possibilities of chance, due to why she is prone to “improvisation”. Socialism in an economically backward country may well be the result of such improvisation. The idea of socialism in general, and of achieving it in Russia in particular, is based on this thesis - about the role of chance and the tendency of history to improvise. This “foundation” determined the most significant differences between “Russian socialism” both from Western socialist utopias and from other socialist models that became widespread in Russian social thought later.

“Russian socialism,” on the one hand, was undoubtedly “inspired” by the national and highly developed patriotic feelings of its founders, on the other hand, it obviously gravitated towards a rationalistic justification, which gave it the features of universality. And the founders of “Russian socialism” themselves did not at all deny paths to socialism other than through the peasant community. An essential feature of “Russian socialism” was the attempt to “build bridges” between the ideal and historical reality. It is important to note one more point: Herzen and Ogarev did not accept Western socialist utopias without criticism. Among the “absurdities” of these teachings they noted most often included the demand for regulation of individual life, the spirit of egalitarianism and leveling. The creators of “Russian socialism” themselves tried to rely on the humanism of Feuerbach’s anthropological philosophy and Hegel’s dialectics, which affirmed the original desire of history for a rational system.

Two years before his death, Herzen gave the following definition of “Russian socialism”: “We call Russian socialism that socialism that comes from the land and peasant life, from the actual allotment and the existing redistribution of fields, from communal ownership and communal management - and goes along with an artel of workers towards the economic justice to which socialism in general strives and which is confirmed by science.”

At the end of the 50s, the ideas of socialism were developed by N.G. Chernyshevsky (1828-1889). His views on the community and on the question of the fate of socialism in the West did not entirely coincide with Herzen’s concept. Chernyshevsky’s model is called “peasant, communal socialism.” The main thing in his theory was the economic justification of the socialist ideal. But even earlier, at the end of the 40s, V.A. Milyutin (1826-1855) wrote a lot about the importance of economic issues for socialist theory. Raising the question of overcoming the utopianism of socialist theories, he emphasized that the latter, if they want to be at the level of science, must solve, first of all, economic issues.

Chernyshevsky highly appreciated the works of Milyutin. Relying in his research on such classics as Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen, using the ideas of Godwin and some of the constructions of Louis Blanc, Chernyshevsky comes to the conclusion: socialism is the inevitable result of the socio-economic history of society along the path to collective ownership and the “principle of partnership” . In order to overcome “dogmatic anticipations of the future,” as he characterized socialist utopias, Chernyshevsky makes the historical process the subject of his research, trying to identify the mechanism of transition from the old to the new, from “today” to “tomorrow.” These searches lead him to the conviction that the transition is based on an objective pattern. Analysis of the historical process and economic development capitalist civilization led Chernyshevsky to the conclusion that the vector of the latter is the growth of large-scale industry and the increasing socialization of labor, which in turn must necessarily lead to the elimination of private property. Chernyshevsky was confident that there was no need to fear for the future fate of labor, since the inevitability of its improvement lies in the very development of productive processes. However, the conclusion reached did not shake his faith in the Russian community.

He associated his ideal of property with state ownership and communal ownership of land, which, in his opinion, “strengthens national wealth much better than private property.”4 But most importantly, they correspond to the liberation of the individual, for the basis of the latter is the union of worker and owner in one person.

For his ideas and ten years of active propaganda work, Chernyshevsky paid with 19 years of hard labor. Imprisoned in solitary confinement in the Peter and Paul Fortress before his sentencing, he wrote the novel “What is to be done?”, where he outlined the contours of the future society and brought out literary heroes who became the prototypes of those “new people” who, some time later, formed numerous detachments of Narodnaya Volya. The further evolution of Russian utopian socialism will be inextricably linked with their practical activities, and it itself will receive the name populist.

Thus, moving in line with utopian socialism, Chernyshevsky made a huge step forward compared to his predecessors. Firstly, in predicting the future he went beyond the boundaries of abstract dogmas and reasoning. Turning to political economy and studying the laws of history gave him some advantages in “drawing” the future society, in particular its socio-economic, spiritual and moral contours. For him, socialism is a type of organization of social life that gives independence to the individual person, so that in his feelings and actions he is more and more guided by his own impulses, and not by forms imposed from without. Secondly, having posed the question “What to do?”, Chernyshevsky gave his answer to it, linking the implementation of the socialist ideal with the peasant revolution, although carefully prepared by the propaganda of socialist ideas among the masses. A necessary condition for a successful popular revolution is its “proper direction,” which can only be carried out by organizations of revolutionaries capable of preparing the people for conscious revolutionary actions. Chernyshevsky, thus, opened the way for combining socialist theory with revolutionary practice - from a fact of social thought, socialism became a factor in the revolutionary struggle. The time of the revolutionary underground and active propaganda of socialist ideas began, a new period began in the development of Russian socialist utopian thought: the ideas of socialism were transferred to the level of applied developments, mostly related to the tactics and strategy of the revolutionary struggle. The socialist utopia has united with the Russian revolutionary liberation movement, and from now on they will act in the same stream.

In the 30s of the XIX century. ideas of utopian socialism begin to develop in Russia. Utopian socialism is understood as the totality of those teachings that expressed the idea of the desirability and possibility of establishing a social system where there will be no exploitation of man by man and other forms of socialist inequality.

Utopian socialism differed from other utopias in that the idea of general, true equality was born and developed in it. It was supposed to build this ideal society on the basis or taking into account the achievements of material and spiritual culture that bourgeois civilization brought with it. A new interpretation of the social ideal: coincidence, combination of personal and public interests. Socialist thought took special forms in Russia, developed by Russian thinkers who wanted to “adapt” the general principles of socialism to the conditions of their fatherland. The inconsistency was manifested primarily in the fact that the main form of utopian socialism in Russia naturally turned out to be peasant socialism (“Russian”, communal, populist), which acted as an ideological expression of the interests of revolutionary and democratic, but still bourgeois development.

The founder of Russian socialism was Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (1812-1870). Herzen associated his spiritual awakening with the Decembrist uprising. The “new world” that opened up to the fourteen-year-old boy was not yet clearly conscious. But this uprising awakened in Herzen’s soul the first, albeit still vague, revolutionary aspirations, the first thoughts about the struggle against injustice, violence, and tyranny.

“The awareness of the unreasonableness and cruelty of the autocratic political regime developed in Herzen an insurmountable hatred of all slavery and arbitrariness” 7.

Herzen was of great interest in the philosophy of history. In the early 40s he comes to the conclusion that where there is no philosophy as a science, there cannot be a solid, consistent philosophy of history. This opinion was associated with the idea of philosophy that he formed as a result of his acquaintance with the philosophy of Hegel. He was not interested in the theoretical basis of philosophy; it interested him insofar as it could be applied in practice. Herzen found in Hegel's philosophy the theoretical basis for his enmity with the existing; he revealed the same thesis about the rationality of reality in a completely different way: if the existing social order is justified by reason, then the struggle against it is justified - this is a continuous struggle between the old and the new. As a result of studying Hegel's philosophy, Herzen came to the conclusion that: the existing Russian reality is unreasonable, therefore the struggle against it is justified by reason. Understanding modernity as a struggle of reason, embodied in science, against irrational reality, Herzen accordingly builds an entire concept of world history, reflected both in the work “Amateurism in Science” and in “Letters on the Study of Nature.” He saw in Hegelian philosophy the highest achievement of the reason of history, understood as the spirit of humanity. Herzen contrasted this reason embodied in science with unreasonable, immoral reality.